Table of Content

Content

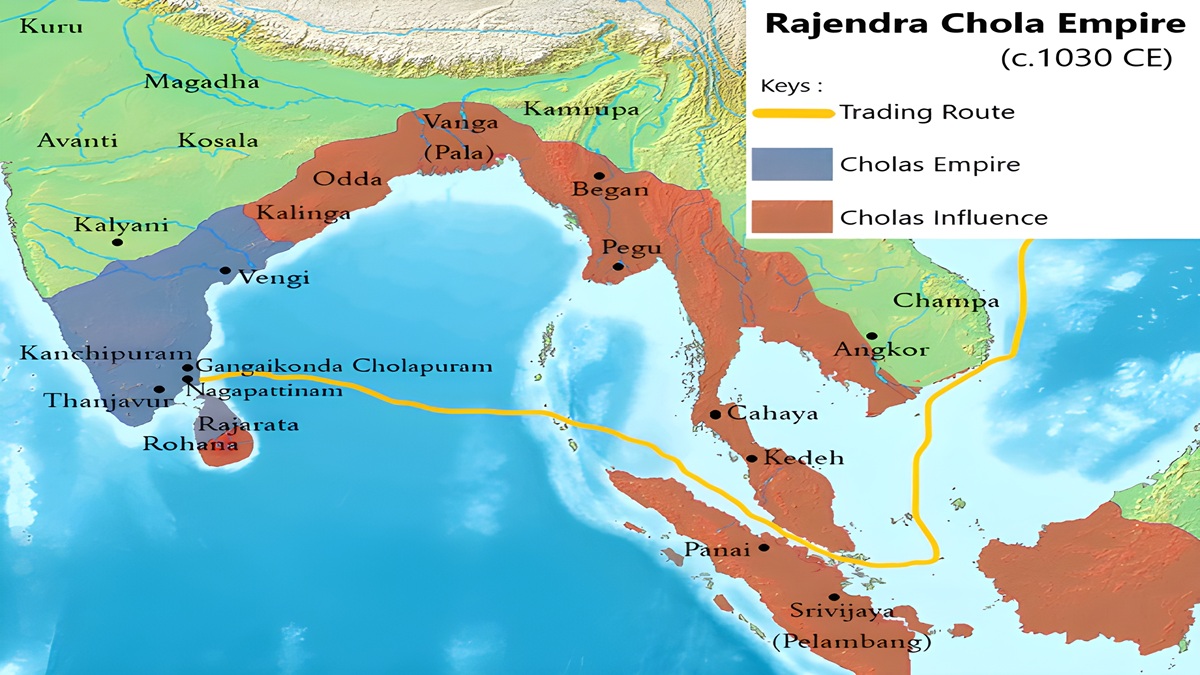

In the era of Chola Empire:: A thousand years ago at dawn, Nagapattinam Harbour on the Coromandel Coast was like a gathering place for the entire world to assemble. Heavy-laden dhows and sturdy ocean-going vessels rode the swells while porters transported bags of pepper, rolls of cotton fabric, jars of aromatic oils, and bronze images to ships at anchor. Sailors were busy adjusting sails and checking navigational instruments. The merchant guild representatives were quarreling amongst themselves about prices for their respective products, while envoys from various distant courts were negotiating for protections and privileges for their respective nations. In the distance, a line of Chola warships indicated that the Empire had arrived, and these were the same ships that would soon sail across the Bay of Bengal, striking at kingdoms that had long thought they could remain safe from an invasion because of the islands that surrounded them.

The Chola’s story I am unfolding is one less popularized by guidebooks devoted to temple towers and bronze sculptures. In addition to their exceptional architecture and sculpture, the medieval Chola dynasty of South India (specifically during the 10th–12th centuries) established an extensive maritime empire that completely transformed life across the Indian Ocean with its vast military forces, commerce and commerce networks, and diplomatic capabilities. The remainder of this piece will provide a comprehensive, evidence-supported history of how an inland kingdom became one of the first Asian blue ocean powers and the significance of its still-existing maritime legacy.

From River-Kings to Sea-Lords: A Brief Historical Frame

The Chola dynasty of India is one of the oldest documented dynasties. Numerous references to the Cholas have been found in Sangam Era texts (and other later written records). The Chola dynasty began its political resurgence during the 9th century CE with a dramatic shift from agriculture to maritime domination of the region known as Tamilakam, which was mostly populated by Tamils. Two of the historical figures most closely associated with the rise of the Chola Empire are Rajaraja Chola I (c. 985-1014 CE) and his son Rajendra Chola I; these two men were responsible for establishing, expanding, and consolidating the power of the Cholas outside of India as well as building and expanding many monumental structures and increasing the long-term effectiveness of the Chola government through their building programme.

The Kaveri delta—the Chola heartland—was not just very fertile and densely populated, however it had strong irrigation systems as well. This excess production supported all kinds of temple building, maintaining armies, ship building, etc. The temples also helped to make the economy: they served to accumulate wealth, coordinated craftspersons, and financed trading. Therefore, having the resources and administration structures in place, the Cholas were in a position to support long-term efforts toward naval operations and the developing of diplomatic relations beyond India.

Strategic Motives Behind Chola Maritime Policy

A simple strategic calculus pushed the Cholas to master the ocean:

- Trade: South Indian goods—especially textiles and spices—were in high demand across the Middle East and East Asia. Controlling maritime routes meant controlling revenue.

- Security: The Bay of Bengal was a contested space. Rivals, pirates, and regional kingdoms regularly threatened commerce and coastal holdings.

- Prestige and diplomacy: Projection of naval power raised the Chola profile, making them interlocutors with faraway courts.

- Ports as power-bases: Thriving ports like Poompuhar (ancient Kaveripattinam) and Nagapattinam generated wealth and served as logistical hubs for both commerce and warfare.

Seen this way, naval development was not optional: it was central to sustaining and extending imperial power.

Building a Blue Water Navy: Ships, Shipyards, and Strategy

The Cholas did not depend on locally improvised ships for naval defense. Archaeological, epigraphical, as well as historical evidence, supports a sophisticated naval infrastructure:

- Shipbuilding: Full-size ships that travel on oceans, strengthened with coir ropes and metal fastenings, to carry soldiers, horses, and cargo.

- Shipyards and ports: Established facilities and harbors in the estuary of the Kaveri River and the Coromandel coast for construction, repair, provisioning, and storage.

- Naval organization: An organizational chain of command that brought together military, harbor, and trade guild representatives to coordinate convoys and excursions.

- Tactical repertoire: Escort duties for convoys, blockades, and amphibious landings during wartime, taking advantage of monsoon winds seasonally.

By the context of the medieval world, it is fair to characterize the Chola maritime force as a “blue-water navy”, that is, a state fleet which functioned far from home-ports and was able to conduct long-range operations—a capability exceedingly unusual in South Asia during this period.

Campaign to Srivijaya: A Naval Blitz That Echoed Across Asia

The best illustration of the Chola’s sea mightiest moment is Rajendra I’s expedition in 1025 C.E against Srivijaya—the famous Sumatran state that ruled over all trade through the Straits of Malacca. For centuries, Srivijaya had been the maritime power of Southeast Asia; it controlled the chokepoints for trade between China and the Indian Ocean by collecting customs duties and controlling trade routes. During this expedition, Rajendra’s fleet sailed through the Bay of Bengal to make a direct attack on Srivijaya’s ports located in both Modern-Day Sumatra and Modern-Day Malaysia and returned with both prisoners and treasure. Although the original purpose of this expedition was not the annexation of territory, it did succeed in undermining Srivijaya’s economic power and showed that the Chola were as strong as their rivals at sea. Contemporary writers and later historical accounts all confirm that this expedition was highly successful and caused significant changes to many areas of Southeast Asia in both the political and commercial spheres.

The consequences were profound: Srivijaya’s strength declined, Tamil traders experienced more liberal access to Southeast Asian trade centres, and the power dynamics of the eastern Indian Ocean moved toward India. Additionally, this raid sent an impactful diplomatic signal—Chola power could reach beyond thousands of kilometres through sheer naval might.

Trade, Guilds, and the Engine of Wealth

The Chola dynasty relied heavily on trade, supplying both a means to maintain economic strength and the basic support of their trade network throughout their empire. Ports located in places such as Poompuhar, Nagapattinam, and Arikamedu linked the Tamil regions (Tamil Nadu) to many places, including Arabia, East Africa, China, and Southeast Asia. The exports from the Chola dynasty included high-quality cotton textiles (one of the primary goods traded to the Middle East and China), pepper, spices, pearls, and many bronze sculptures or images. The trade imports for the Chola dynasty included gold, Chinese ceramics, Arabian stallions, and luxury items.

As a key factor in the Chola’s maritime success, the merchants had to be organized through merchant institutions. Tamil merchant guilds such as the Ayyavole 500, Manigramam, and Anjuvannam were like the multinational corporations of today because they were not only owners of their vessels but they also financed their voyages and kept their goods in stores while also having local privileges negotiated for them. They created long-lasting networks of Tamil traders in the Southeast Asian ports, which allowed for both continuity of commerce and for the flow of information even if the conditions at home changed. The inscriptions and other records on both sides of the Indian Ocean show how large and organized these merchants were.

Soft Power on the Tide: Religion, Art, and Cultural Exchange

The Chola Empire exported an extensive range of commodities and military capability but did not stop there; they also exported cultural knowledge, artistic techniques, and political institutions. This entrepreneurial spirit within the Chola Empire led to the “migration” of a multitude of skilled craftsmen, such as priests, artisans, and traders. These skilled workers carried with them their religious beliefs, such as Shaivism (Hinduism) and local Buddhist traditions, architectural construction techniques, and the aesthetic of the alloying process of bronze. The influences of Chola style created an influx of Chola-style iconography and temple layout in areas throughout Southeast Asia. Travelling from southern India to places like western Sumatra, eastern Singapore, and throughout parts of the eastern Malay Peninsula, there are remnants of Tamil inscriptions, i.e., in stone and copper plates. Additionally, portable artifacts, particularly luxurious examples of Chola bronze such as the idolized image of Nataraja, became status symbols in kingdoms and cities throughout the world.

Cultural transmission was two-way: Southeast Asian goods, motifs, and religious ideas penetrated Tamil society too, enriching its artistic vocabulary and expanding its maritime imagination.

Administration, Temples, and the Record-Book Empire

The Cholas’ administrative achievements were an essential backbone for maritime strategy. Their governance model balanced local autonomy with imperial integration

- Village and town assemblies (Ur, Sabha, Nagaram) retained significant local powers over land, irrigation, and resources.

- Temple institutions functioned as banks, landholders, employers, and sponsors of craft—central nodes in economic life.

- Revenue system: well-documented land surveys and bounded tax categories underpinned predictable income streams.

- Record keeping: an extraordinary abundance of inscriptions—on temple walls, copper plates, and stone—preserves grants, naval deeds, merchant privileges, and administrative orders.

Due to this extensive collection of documentary sources, it is possible to provide detailed accounts of aspects of Chola economic and maritime history much earlier than other state systems. The temples themselves, such as the popular Brihadeeswarar (Brihadisvara) Temple located at Thanjavur, are the material embodiments of these industries—administrative, economic, and artistic—and are considered among the world’s most UNESCO-recognized examples of Chola statecraft and devotional patronage.

Why the Maritime Empire Waned

The Chola maritime ascendancy was not immortal. From the late twelfth century, a complex mix of factors eroded their position:

- Regional rivals (notably the Pandyas and later the Hoysalas) reclaimed territory and challenged Chola hegemony on land.

- Changing trade patterns and the emergence of new regional centres altered the economic map of the Indian Ocean.

- Internal stress—successional disputes, resource strains from prolonged campaigns, and the limits of centralized control across vast maritime distances—reduced imperial agility.

By the later thirteenth century, Chola political power had faded as a dominant imperial force, though their cultural imprint and the institutions they had shaped persisted for centuries.

Enduring Legacies

The Chola maritime story matters for several reasons:

- It reframes medieval Indian history: the peninsula was not inward-looking; it engaged robustly—economically and militarily—with the wider oceanic world.

- It demonstrates the synergy of trade and force: naval power without commerce is brittle; commerce without protection is vulnerable. The Cholas married the two.

- It underlines administrative sophistication: decentralized local governance, temples as economic organs, and meticulous record-keeping made sustained maritime projection possible.

- It reveals cultural entanglement: art, religion, and language flowed along the same routes as cotton and spice, making the Indian Ocean a dense web of interaction rather than a periphery.

Recovering a Sea-Held Past

Although the Chola dynasty is best known for its beautiful temple buildings (with soaring vimanas), exquisite lyrical poetry, and bronze sculptures, to consider them only as temple builders would be to overlook the other half of their heritage. The Cholas’ empire was based on an interconnected series of systems that spanned the world, using ships and traders to carry goods and power, prestige, and ideas around the globe for two hundred years.

In ruined harbours, temple inscriptions, and bronzes that have traveled far, the evidence remains: centuries before modern navies and global commerce redefined the world, the Cholas were building an Indian Ocean order of their own. Reclaiming that maritime past enriches our understanding of medieval Asia and reminds us that India’s ties to the sea are ancient, strategic, and deeply woven into its civilizational fabric.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS/