Table of Contents

Contents

A national anthem crystallizes the essence of a country; its history, beliefs, and collective aspirations. The national anthem of India, “Jana Gana Mana” has a significant role in shaping that emotional attachment. Whenever it is sung in school gatherings at sunrise, in crowded sports arenas before a cricket game, or alongside the ceremonial hoisting of the tricolour, it projects feelings of love for the country and brings people together despite their different languages, cultures, and beliefs. This article explores every aspect of the national anthem of India-its history, the moving lyrics of the national anthem, adoption, music, symbolism, legality, controversies, and occasions on which it is prescribed to play the anthem!

Origins and Authorship

Composer: Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1913)

Date of Composition: 11 December 1911

Context: Composed originally as a part of a five-verse hymn called Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata, it came into existence amidst rising nationalist feelings against the partition of Bengal (1905) and the peak of the Indian struggle for freedom.

First Performance: On 27 December 1911, during the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress, Tagore’s niece Sarala Devi Chowdhurani sang the hymn accompanied by a chorus of schoolchildren.

Myth vs. Reality: Unlike one of the most common myths, Jana Gana Mana was not written to honor King George V at the Delhi Durbar. Historians concur that it celebrates the spiritual unity and destiny of India itself.

The history of India’s National Anthem starts with one of the greatest literary heroes in India’s past — Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore was a poet, writer, composer, and philosopher born in 1861. He was the first Asian to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. “Jana Gana Mana” was written by him originally in Sanskritized Bengali — a Bengali highly inspired by Sanskrit.

The anthem was publicly sung for the first time on 27 December 1911 at the Indian National Congress annual session held in Calcutta. It was written a few weeks before, on 11 December 1911. The song was sung by a school group of children under the leadership of Tagore’s niece, Sarala Devi Chaudhurani.

A turning point in the anthem’s musical path came in February 1919 at Besant Theosophical College in Madanapalle, Andhra Pradesh. Tagore translated the first verse of the hymn “Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata” into English under the Title “The Morning Song of India”, and Margaret Cousins, wife of the principal of the college, laboriously notated its melody in Western notation with the consent of Tagore. This bilingual edition guaranteed that both the original Bengali and India’s national anthem in English could be performed accurately and kept safe for future generations.

Lyrics and Translation

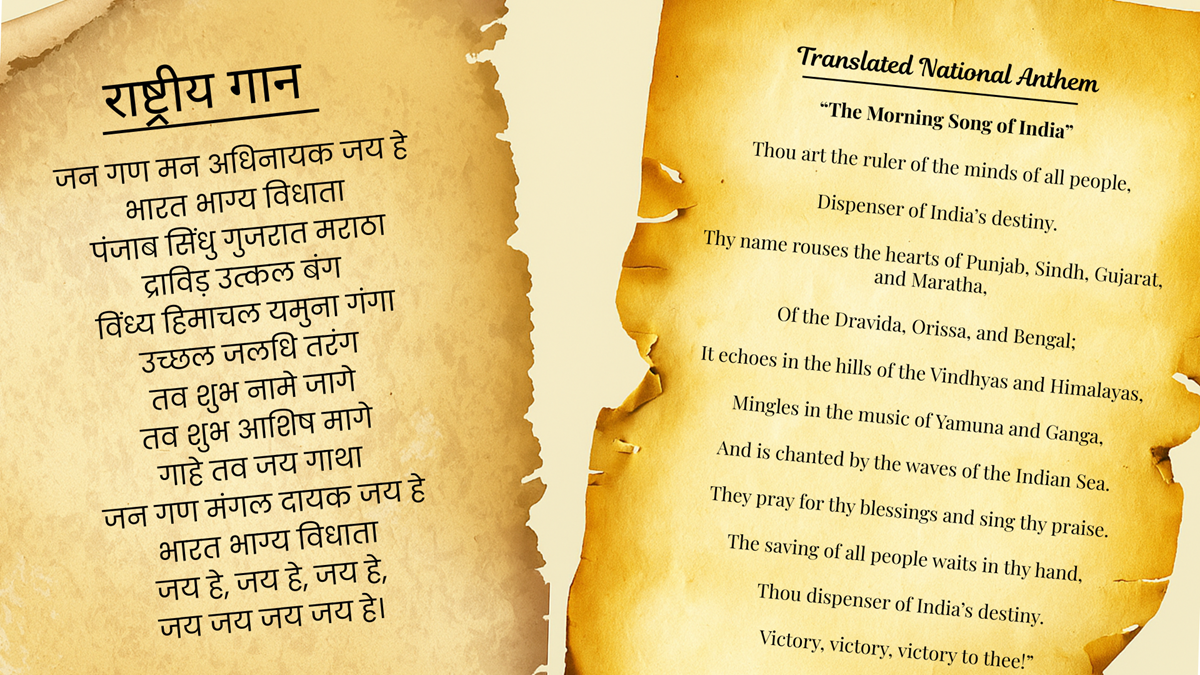

Only the first stanza of the original five-verse Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata was adopted as the National anthem of India.

Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka, jaya he

Bharata-bhagya-vidhata

Panjab-Sindhu-Gujarat-Maratha

Dravida-Utkala-Banga

Vindhya-Himachala-Yamuna-Ganga

Uchchala-Jaladhi-Taranga

Tava-Subha-Name-Jage

Tava-Subha-Aśhisha-Mage

Gahe-Tava-Jaya-Gatha

Jana-Gana-Mangala-Dayaka Jaya He

Bharata-Bhagya-Vidhata

Jaya He, Jaya He, Jaya He

Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya He

Translation of the National Anthem of India in English

“The Morning Song of India”

Thou art the ruler of the minds of all people,

Dispenser of India’s destiny.

Thy name rouses the hearts of Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat, and Maratha,

Of the Dravida, Orissa, and Bengal;

It echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and Himalayas,

Mingles in the music of Yamuna and Ganga,

And is chanted by the waves of the Indian Sea.

They pray for thy blessings and sing thy praise.

The saving of all people waits in thy hand,

Thou dispenser of India’s destiny.

Victory, victory, victory to thee!”

Occasionally, a condensed rendition of the National Anthem is also performed, which includes the verse’s opening and closing lyrics, such as:

“Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka jaya he

Bharata-bhagya-vidhata.

Jaya he, Jaya he, Jaya he, Jaya Jaya, Jaya, Jaya he.”

This translation of the Indian national anthem interweaves a sense of reverence, geography, and philosophy. Tagore names various areas of the subcontinent – Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat, Maratha, Dravida, Orissa, Bengal – as a way to invoke India’s unity in diversity, a cornerstone of the nation’s identity.

Adoption as the National Anthem

Official Adoption: On 24 January 1950, the Constituent Assembly of India formally chose Jana Gana Mana as India’s National Anthem, two days before the Republic on 26 January. Jana Gana Mana, which was originally written in Bengali by Rabindranath Tagore, was adopted in the Hindi version for nationwide use based on the linguistic solidarity of the multicultural country.

Although it had been used in public events since the early 20th century, on 24 January 1950, “Jana Gana Mana” became the National Anthem of India in the official acceptance by India’s Constituent Assembly. “Vande Mataram,” the national song, was also presented as an option, but the Assembly chose “Jana Gana Mana” instead because it is secular, short, and inclusive in its nature. The anthem was also included in the annex that contains the Constitution of India, and as such, this declared the anthem to have constitutional validity from the date of adoption.

Why Not Vande Mataram?

- Vande Mataram, the revered national song, was a strong contender.

- But its references to the “Mother Goddess” and Hindu iconography caused the Assembly to prefer Jana Gana Mana for being secular and plural in tone.

Prior to the formal adoption, it had already received praise for its tone and its dignified presentation of Indian representatives, as it was performed before the United Nations General Assembly in late 1947, before an international audience.

Musical Composition and Rendition

- Melody: Tagore himself composed the melody, setting it in Raga Alhaiya Bilaval. His grand-nephew, Dinendranath Tagore, likely assisted in formalizing the tune.

- English Notation: Crafted by Margaret Cousins in Madanapalle in 1919 with Tagore’s approval to make sure it was transcribed accurately as a melody.

- Standard Orchestration: Adapted and arranged by Captain Ram Singh Thakur of the Indian National Army in 1942, so it could be sung in collective performances, especially during the freedom struggle.

Authorized Durations:

- Full Version: Approximately 52 seconds, typically used at flag ceremonies and formal state events.

- Short Version: About 20 seconds, incorporating only the opening lines, used in brief observances or informal settings.

Performance Protocol: As per Home Ministry guidelines:

- Tempo: ~76 beats per minute

- Key: C major

- Preceded by: A drum roll (for band performances)

- Bracketed by: Silence before and after

- Audience Conduct: Standing at attention, removing headgear, and observing respectful silence.

Legal Guidelines and Respect Protocol

The National Anthem is safeguarded under the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971. As per this act:

- Any wilful disrespect for the anthem will be punishable by a maximum of three years imprisonment, a fine, or both.

- Citizens must stand at attention when the anthem is being played, except in cases involving physical disability.

- The Supreme Court of India in 2016 required that movie theaters play the anthem before every showing. Then it modified this requirement in January 2018, and held that showing the anthem was optional for theater owners, but under the Court’s holding, if the anthem was played, everyone was to stand except persons with disabilities as required under the Home Ministry’s guidelines under Article 51A(a).

Instructions are given from time to time by the Ministry of Home Affairs specifying when and how to play the anthem. These instructions emphasize respect, posture, and the right environment.

Occasions for Playing the National Anthem

Based on official Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) guidelines, Supreme Court precedents, and common practice in India, the occasions on which the national anthem can be played are clear, finite, and exhaustive under existing law and guidance, and any change would require formal amendment.

Full Version (Approximately 52 seconds)

- Flag hoisting/unfurling ceremonies: Republic Day, Independence Day, state government events.

- Military and civil investitures: Presentations of regimental colours, honour salutations, and ceremonies involving the President or the Governor.

- Arrival/departure of the President at formal State functions.

- Salute to the President or Governor in their respective offices or fields.

- Outside Radio Address by the President: Before/after addresses on All-India Radio.

- Special government-declared occasions: When explicitly ordered by the central or state government.

Short Version (Approx. 20 seconds)

- Unofficial or short events, like school assemblies, where it may not be sensible to play a full version.

- Toasts during military messes and regimental meets as an honour to the country’s prestige.

Public Events and Mass Singing

- Mass gatherings (e.g., national festivals, educational institutions, cultural events): Anthem singing is allowed as long as the appropriate decorum and silent reverence are maintained.

Cinema Halls and Theatres

- Although the requirement for theaters to play the anthem was imposed by the Supreme Court in 2016, it was made optional in 2018. If theatres do choose to play the anthem, audiences must stand and observe silence, except for audiences with disabilities. Audiences are not required to stand if the anthem is a segment of a newsreel or documentary featured in a film.

Abroad by Indian Leaders

- State visits and international summits: When the President or Prime Minister travels abroad, the anthem is performed in arrival or departure ceremonies. Likewise, during Indian embassy functions and diaspora events, it reasserts national identity and pride.

- Commemorative trips and international diaspora festivals also include the anthem as part of cultural assertions.

Controversies and Clarifications

A protracted controversy exists surrounding Jana Gana Mana, alleging that Rabindranath Tagore wrote it in 1911 to honor King George V during the King’s visit to India and the Delhi Durbar. This misunderstanding came about because the song debuted on December 27, 1911, at the Indian National Congress session in Calcutta, soon after the King was proclaimed Emperor of India.

Colonial English newspapers, for example, The Statesman and The Englishman, reported the news falsely, stating that Tagore had written the song for the King. In reality, two different songs were performed that day — one entitled “Badshah Humara” in the context of honoring the King, and Jana Gana Mana, a spiritual hymn invoking the “Dispenser of India’s destiny,” and not any monarch.

Tagore’s Clarification

Years after the incident, Tagore was compelled to respond to this misconception. In letters written in 1937 and 1939, he addressed the controversy with clarity and conviction.

In a famous letter written in March 1939, Tagore wrote:

“A certain high official in His Majesty’s service… wanted me to write a song of felicitation towards the Emperor… I pronounced that I shall never address my poem to any earthly king. It was addressed to God. When I sang it, people knew it was not meant for George the Fifth.”

He further added:

“I should only insult myself if I cared to answer those who consider me capable of such unbounded stupidity as to sing in praise of George the Fifth or the Sixth. That kind of loyalty I can never pretend to feel, even if I had to.”

These powerful words directly confront the notion that Jana Gana Mana was a tribute to colonialism. It was made very clear by Tagore that the “Bharata Bhagya Vidhata” (Dispenser of India’s Destiny) in the song referred to a divine presence — not a monarch, emperor, or colonial ruler.

Resonance of Unity

India’s National Anthem, “Jana Gana Mana,” represents more than just a song; it’s a living representation of the soul of the country. The poem within sings of India’s geographic richness and cultural unity. With a long and complex past, a dignified tune, and a message that resonates with people of all places and times, the National Anthem truly represents all those who call India home. The National Anthem has inspired generations of Indians to imagine, build, and realize a united, inclusive, and extended India.

From grasping the translation of the Indian National Anthem to knowing how and when to sing it respectfully, every citizen – especially the youth – should interpret the anthem as a reminder to consider our rich heritage and democratic values every day.

Who wrote the national anthem of India?

The national anthem of India, “Jana Gana Mana,” is written by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore.

When was the national anthem “Jana Gana Mana” first sung?

Jana Gana Mana was first sung on December 27, 1911.

When was the national anthem adopted by the constituent assembly?

The national anthem was adopted by the constituent assembly on January 24, 1950.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel : https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS

Thanks for making social media feel meaningful 🌻 and worthwhile for everyone here

This really helped me today

Your work has genuinely made such a positive difference in my entire life 💯

Really well crafted here

Your work has such a lasting positive 🔥 impact on everyone who discovers it