Table of Content

Contents

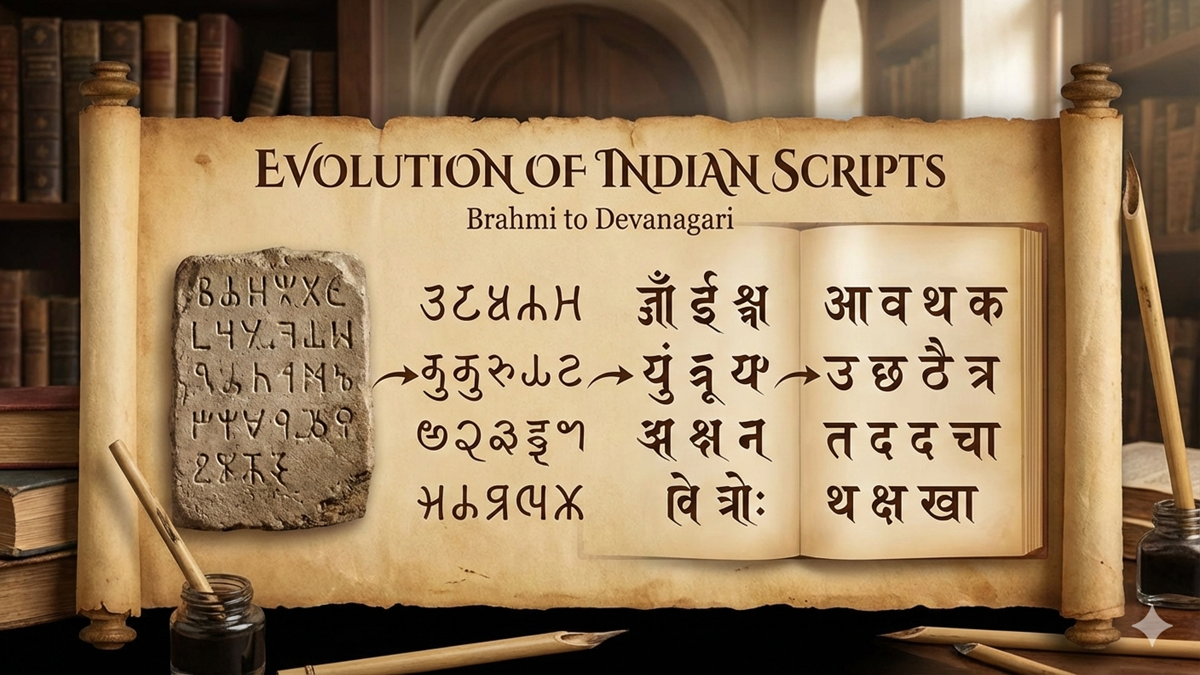

Civilization’s historical memory is recorded through writing. That memory is documented in an extraordinary family of scripts in India — a continuous connection between the Ashokan rock edicts and today’s news headlines on mobile devices. The progression from Brahmi, the earliest widely adopted script on the subcontinent, to Devanagari, which represents today’s Hindi and Sanskrit written forms, is not linear; rather, it reflects an incremental development shaped by various materials and by religion, administration, and localization. The following article presents this progression from an overview, providing context about changing technologies, culture, and people who have helped create letterforms throughout two millennia.

The Birth of Brahmi: India’s Foundational Script

The archaeology confirms that Brahmi was used in the 3rd Century BCE. The edicts of Ashoka (circa 268-232 BCE) etched upon rocks and pillars throughout the subcontinent are among the most iconic historical examples of Brahmi. The inscriptions provide information about the politics of his time and are an essential source for understanding how Buddhist script developed.

Brahmi is considered to be an abugida as each letter within the Brahmi script represents a consonant with an implicit vowel (usually /a/), which can be modified or erased through diacritics or other written symbols. Additionally, Brahmi maintains a consistent structural system based on syllable structure. The characters of Brahmi are geometric and distinct from one another and appropriate for engraving into stone as well as for writing on birch bark or palm leaf. Due to Brahmi’s use to represent dialectal differences between Pali and Sanskrit, many regional variations of Brahmi emerged as a result of local copying practices, which eventually gave rise to new forms of writing.

Scripts Do Not Change Overnight: The Dynamics of Evolution

Script evolution is not static; it is a process shaped by many forces:

- Writing materials: Brahmi was first engraved on stone and metal, thus favoring clear, discrete strokes. The transition to palm-leaf manuscripts and ink on birch bark encouraged smoother, rounded forms because the surfaces and tools influenced the strokes used.

- Writing speed: As administration, religion, literature, and trade expanded, scribes needed faster, more efficient ways to record texts — leading to ligatures and simplifications.

- Linguistic adaptation: Scripts had to be suited not just for Sanskrit or Prakrit, but also for emerging regional languages, requiring innovations in how sounds were represented.

- Cultural prestige and religion: Religious institutions, whether Buddhist, Jain, or Hindu, became centers of literacy; they nurtured and transmitted standard forms as part of scriptural tradition.

These forces interacted over centuries, so the shapes of letters changed slowly and cumulatively across time

From Brahmi to Gupta: The First Major Shift

Between the beginning of the Brahmi and the Gupta script (around 4th to 6th Century), there was a major change in how people wrote. The letters on temples and manuscripts during that time had changed from being angular and separated to being round and compact. As more and more people began to use palm leaves and descriptions to write, they began to use curvy lines and flowing designs to write in ink with pens rather than carving into the stone.

Many of the forms that will later be recognised in the northern Indian script were established during the Gupta period. The consonant form and vowel marking are still used, but in a more streamlined fashion, and scribes begin to experiment with ligatures of consonants when they appear in combination.

Siddham, Sharada, and the Diverging Paths

After Gupta, regional scripts began to crystallise. Two important branches that helped bridge the Gupta forms to later North Indian scripts were Siddham and Sharada.

- Siddham gained popularity in Eastern and Central Asia and was transported along trade and pilgrimage routes to other regions of East and Southeast Asia by Buddhist Scholars who traveled along these routes. In particular, the neat structure of Siddham makes it well-suited for copying Buddhist texts; in turn, the Siddham script, developed by Buddhist scribes, influenced the shapes of many subsequent Indic scripts.

- Sharada emerged in the northwestern regions, primarily Kashmir and Punjab, and it was used primarily for writing in both Sanskrit as well as regional language. Sharada evolved over the years to include features such as distinct conjuncts and vowel signs, as well as the increased use of vertical strokes.

The scripts were the means through which stylistic and orthographic characteristics passed between regions and faiths. The local scribal schools of each region refined letters to make them easier to read and write. This resulted in a family of related scripts that exist today but have a unique style in each area where they are found.

The Emergence of Nagari and the “Headline” Feature

In the first millennium CE, Northern Scripts are now clustered into a grouping called Nagari. Nagari is derived from the word Nagara, which means city or urban place. The Nagari script has been used primarily for administrative purposes in cities and literature. The most significant innovation in the Nagari script is the śirorekhā, or horizontal line above the letters that lines them up visually. The śirorekhā connects letters visually.

Scholars believe that the creation of the headline came about because of how Palm Leaf writing was constructed using a pen and through the use of connecting letters and ligatures. When Scribes created the connected forms, a naturally occurring top line was created. Over time, this naturally occurring line became an intentional graphic convention. The headline serves to unite all the syllables into a single word-block, makes it easier for readers to read lines, and also gives a recognizable graphical identity to many northern scripts.

The Nagari tradition has matured with the introduction of a more sophisticated treatment of syllabic consonant clusters (conjuncts). Due to phonological and compound formation needs (of Sanskrit) necessitating compressed representation of consecutive segments of consonants, creators of script produced combinations of lines (stacks) that were ligatured together in relation to placement; this was a major development of Devanagari.

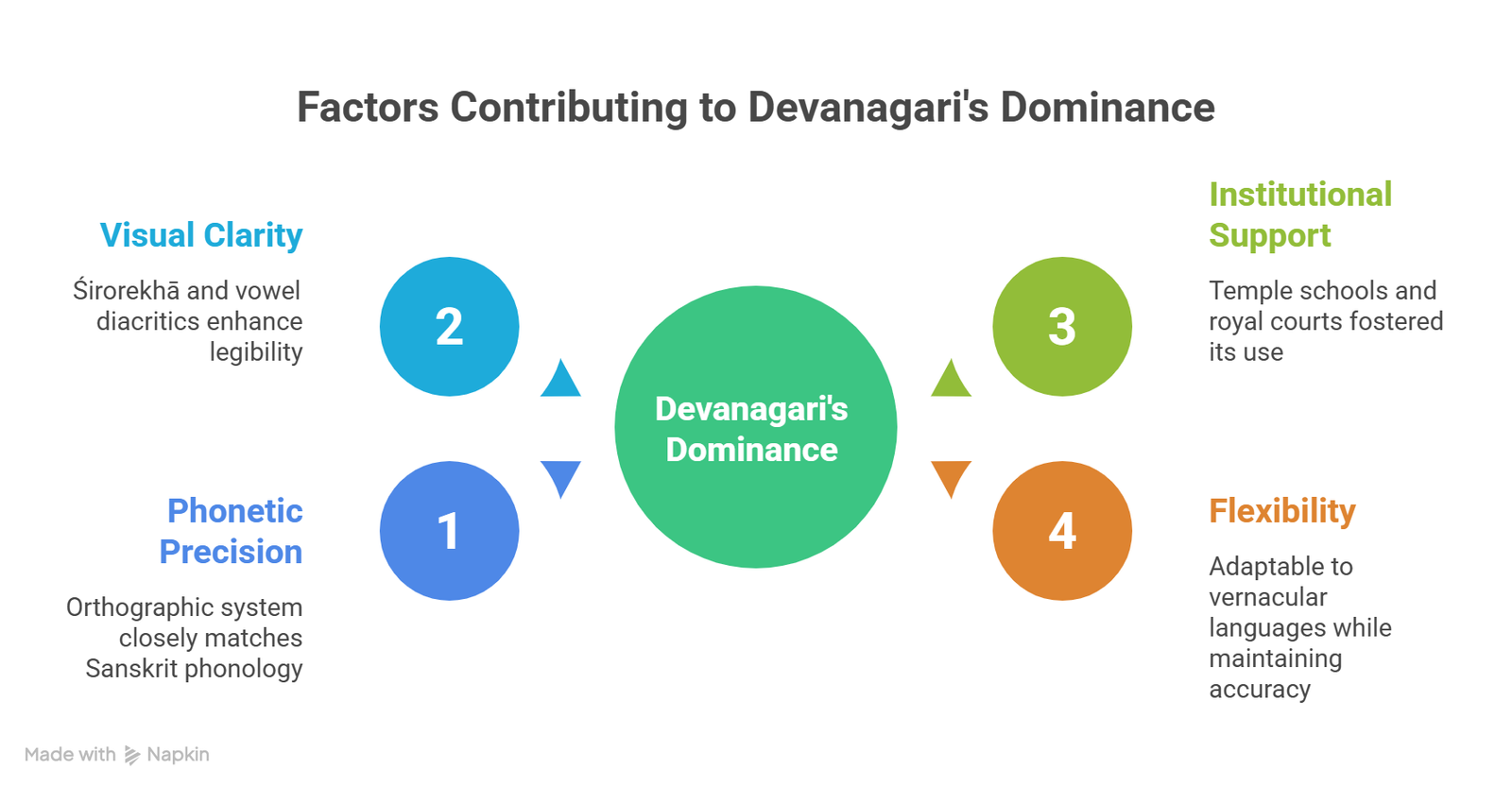

Devanagari: Why It Rose to Prominence

Devanagari is a term (meaning ‘script of the gods’/’script of the city’) originating during the medieval period, indicating a form of written script that had very high social standing. Originally utilized for writing in Sanskrit, it would later become the dominant form of writing for many other languages, including Marathi, Nepali, and Hindi.

- Phonetic precision: Devanagari’s orthographic system matches Sanskrit phonology closely, which made it ideal for preserving liturgical and scholarly recitation.

- Visual clarity: The śirorekhā gives lines of text a stable visual rhythm, and the systematic placement of vowel diacritics around base consonants aids legibility.

- Institutional support: Temple schools, missionary scholars, and royal courts that prized Sanskrit fostered Devanagari forms in manuscripts and inscriptions.

- Flexibility: Devanagari’s mechanisms for ligatures and diacritics allowed it to adapt to vernacular languages while retaining its accuracy for Sanskrit sounds.

Over centuries, scribal standardisation and the prestige of Devanagari in educational and religious contexts cemented its status.

Seeing the Change: Letter-by-Letter Lineage

One straightforward example of how evolution occurs can be seen in the evolution of a single letter. The common consonant, which we often see transliterated as “k” originated as an angular composite letter (or glyph) in the early Brahmi alphabet, where it contains angular strokes ideal for chiseled lettering onto stone. By the time this same letter reached the Gupta Period, it evolved into a rounded, compact shape. When this letter appears in an early example of Nagari or Devanagari documents, its shape continues to evolve with smoother and more harmonious curves designed to fit under the headline of every page when written.

Likewise, the way vowels are represented continued to change over time. In the early forms of the Brahmi script, some vowels were represented distinctly; however, later forms of the script began to use diacritical marks that appear attached directly to consonants, or can even be written around them — e.g., the short “i” (इ) mark is shown as appearing before a consonant but is pronounced after it. Devanagari also changed the way conjuncts (like kṣ (क्ष), jñ (ज्ञ), etc.) were formed from groups of multiple characters into more cohesive ligatures.

Structural continuity is the key characteristic present regardless of the visual format in which it appears. The different stages share an orthographic function; that is, they all demonstrate the consonant + vowel pattern, with each stage containing clusters. However, the orthographic presentation at each stage differs due to their construction materials, the speed at which they were made, and the aesthetic of the area.

Religion, Learning, and the Spread of Scripts

In India, religious and educational institutions have long been central to the copying and preservation of written works. The Buddhist monasteries, Jain libraries, temple schools, and royal archives functioned as the principal sources of copying these materials. By travelling along the pilgrimage routes and trade routes, Monks and Scholars were responsible for disseminating the various styles of script. Siddham scripts travelled with Buddhist Missions to the East, and Sanskritic Nagari literature spread throughout Northern India via temples and courts.

As Sanskrit, due to its use in high ritual as well as scholarship, had scripts that could precisely record its sounds, the result was the establishment, preservation and teaching of those scripts. This clearly indicates how the prestige of Sanskrit allows for the condensation of attention and standardisation to specific script forms (such as Devanagari).

Devanagari in the Modern World

Following the end of the numerous centuries-old manuscript versions of Devanagari’s story was portrayed in numerous types and styles of printed versions during the print revolution beginning in the 19th century into the 20th century. With this increased demand for printed content, the glyphs of Devanagari are all standardised into a uniform form, which also allows accurate conjunct formation for Devanagari letters; in today’s world, the advent of Unicode has created a strong and uniform encoding mechanism for the Devanagari alphabet to enable the use of digital typesetting, web publishing, and mobile texting.

The Devanagari script is currently everywhere; it can be found in books that are taught in schools, newspapers, road signs, websites, and social media etc., through the revival movement as well as research by scholars, via studying these older forms of writing (such as Brahmi-Sharada-Siddham) and connecting their findings with paleography, philology, and the history of the culture. The bold top line of the Devanagari script is an easily identifiable graphic element representing several North Indian languages in the modern world.

Why Understanding Script History Matters Today

Why should a modern reader care how Brahmi evolved into Devanagari? There are several reasons:

- Cultural continuity: Scripts connect us materially to the texts that shaped social and religious life for millennia.

- Linguistic insight: Knowing script history clarifies why orthographies are the way they are and how phonetics and writing interact.

- Preservation: Awareness fuels efforts to conserve manuscripts, decipher inscriptions, and digitise threatened traditions.

- Identity: Scripts are markers of group identity, carrying aesthetic, regional, and spiritual associations.

For students of history, language enthusiasts, and anyone curious about India’s past, script history offers a clear window into how ideas moved across space and time.

Conclusion: From Stone Inscriptions to Smartphones

The progression of the written word from the early Brahmi scripts on rocks to modern-day Devanagari displayed on our mobile devices has been driven by many different forces over a period of approximately 2,000 years. These include cultural and technological evolution and developments through trade and commerce, as well as the traditional methods used by scribes throughout history that shaped their art. Along with other established script traditions, the written forms have maintained their core structures while being able to adapt themselves to the changing nature of our media and means of communication.

At the end of the day, the development over time of the Indian writing systems serves as a good reminder that all writing systems are evolving entities — they capture and preserve aspects of our collective history while concurrently changing and developing to meet the needs of contemporary society. All of the articles, newspapers, and journals that we read today in Devanagari connect, possibly without direct visual evidence, to the days when scribes painstakingly carved government decrees on stone tablets, monks used lit candles as illuminations to reproduce sacred texts, and university professors fashioned the styles used by future generations to convey their thoughts via writing.

Read More Article: India’s Maritime Superpower , Pattachitra , National Emblem of India

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS/