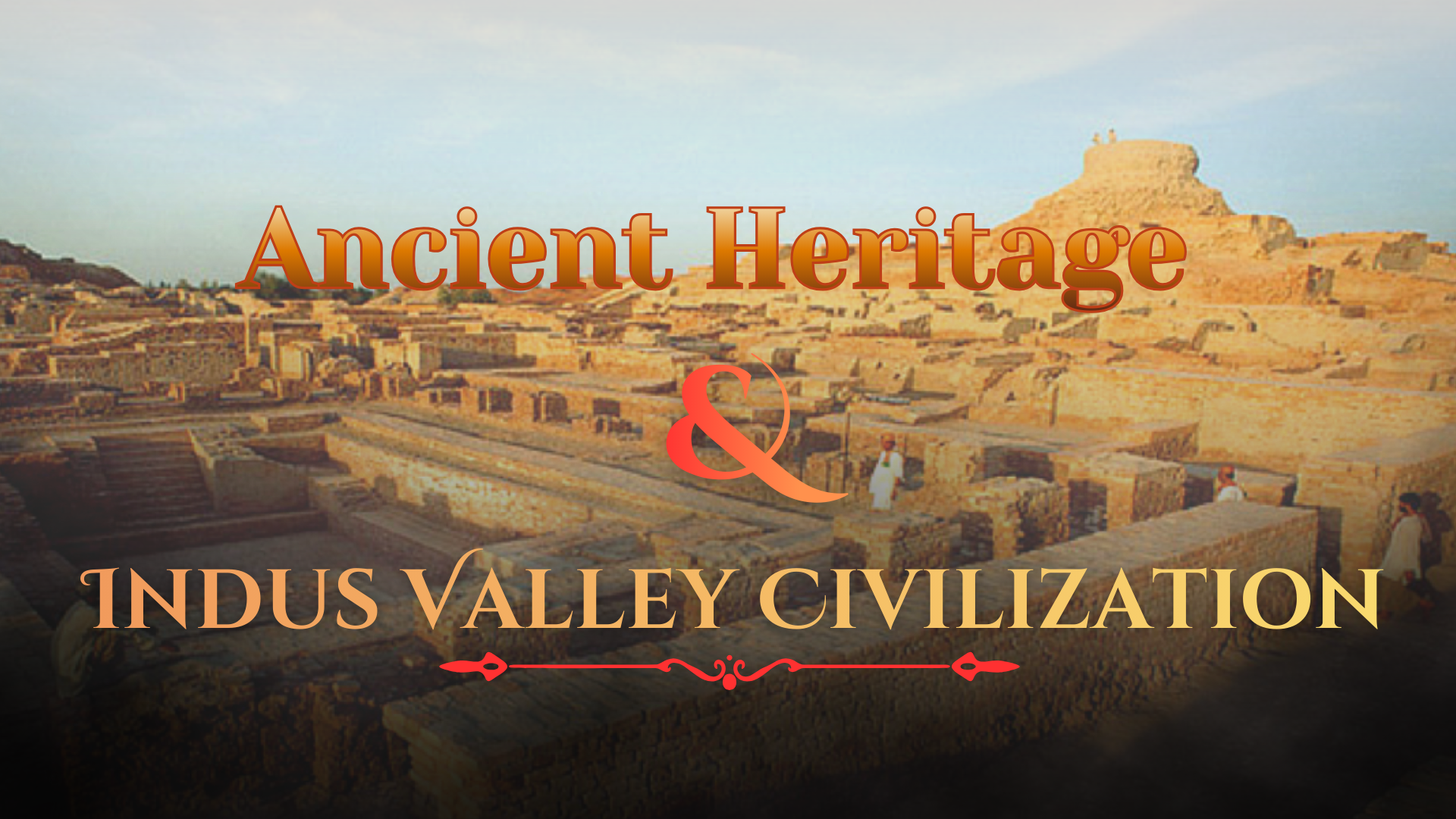

The Indus Valley Civilization (also referred to as the Harappan Civilization) emerged along the river plains of South Asia over 4,000 years ago, and within a few centuries, much of its grand cities had disappeared. These cities, which included straight roads, covered drainage systems, and uniformity in the use of bricks, are some of the most mysterious archaeological finds in human history. In this article, we provide some of the most important pieces of evidence we have regarding the Indus Valley, as well as questions that arise from the evidence we have. These questions continue to motivate historians, archaeologists, scientists, and others to research, analyze, and speculate.

A Short Timeline and the Major Sites

The Indus Valley Civilization flourished in the region from approximately 3300 to 1300 BCE, reaching its peak technological and urban sophistication during the Mature Harappan period (2600–1900 BCE). During this era, major population centers such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, and several other sites emerged across the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. These cities were planned with remarkable precision: streets and alleys followed grid patterns with consistent widths, and buildings were constructed using standardized rectangular bricks.

In addition to their architectural uniformity, ancient Harappan civilization’s cities featured advanced waste-management systems that were exceptionally developed for the Bronze Age. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Harappans maintained a strong agricultural base, produced finely crafted goods, and engaged in long-distance trade networks. Yet, despite their achievements, much about their social structure, belief systems, and daily life remains unknown, leaving the Indus civilization one of history’s most intriguing mysteries.

That geographical spread and chronological depth make the Indus civilization comparable in scale to contemporary Egypt and Mesopotamia — yet its record is frustratingly different because it left no long, readable texts.

1) The undeciphered Indus script — the largest blind spot

The Indus script is probably the most frustrating problem facing historians. Thousands of inscriptions exist, mostly on small seals and pottery, and other objects, but most are very short (only a few characters long), and there is no bilingual context (similar to the Rosetta Stone) to aid interpretation. Estimates of the total number of different symbols range from several hundred to several hundred; most historians agree that there are approximately 400-600 symbols. However, historians are still trying to determine whether the Indus script was a true form of writing, a collection of religious or administrative symbols, or a logo-syllabic (combined letter/symbol) method of written communication.

Why this matters: The Indus Civilization did not leave behind any decipherable text, and therefore, we can never be absolutely certain how they understood God, Law, Kinship, Government, and the way of trading (not even the name they gave their city), all have to be determined through indirect evidence. The resultant evidence has resulted in conflicting explanations and ideas.

2. Urban planning that implies coordination — but no palaces

When visiting the ruins of Mohenjo-daro or Harappa, you cannot help but notice how neatly organized they were. The layout consisted of streets arranged in a grid pattern, with houses built in blocks. Many of the houses have their own wells and private bathrooms, as well as drains that ran alongside the streets. The city’s public buildings (Mohenjo-daro’s Great Bath, for example) are located on top of “citadel” platforms, along with large structures used for storing grain. However, there have not been any palaces or tombs discovered by archaeologists that indicate an organized, centralized form of government, in contrast to what was found in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt at the same time.

As there is no evidence of a strong and visible king enforcing technical standardization and urban coordination, this absence raises the major question of how did it occur and persist across a multitude of cities? A number of theories have been suggested as to how this may have been achieved: through a civic or municipal bureaucracy, through networked merchant guilds that enforced common standards of operation, through ritual authorities (priests or priestly councils) acting as the enforcers of ritual traditions, or through decentralized city-states (i.e., city-states with common technical traditions) connected to one another by trade and community links. However, there is no textual basis to confirm any of these theories, and therefore all theories must be considered equally plausible, with the potential that the social realities were different regionally or over time.

3. Standardization at an extraordinary scale

One of the more fascinating and still puzzling things is how the same types of technology were distributed over long distances. Consistent ratios of bricks (usually thought of as a 1:2:4 ratio), weights made from stone (graduated weights), and seals with the same symbols and designs are found at places located hundreds of kilometres apart.

Such a high degree of standardization suggests ongoing interactions and regulatory systems, including common trade practices, common manufacturing practices, and possibly traveling craftsmen or official inspectors that are responsible for upholding quality control. Yet we cannot see those agencies in the archaeological record. In other words, the Indus Valley took standardization very seriously, but to this day, we have no idea who actually regulated it.

4. The Great Bath and water engineering

Mohenjo-Daro’s Great Bath is known worldwide for its beautifully constructed, sealed pool with surrounding rooms and steps, and evidence of an advanced method of supplying and removing water. Houses throughout the key cities of the Indus Valley had wells inside; drains were closed for health concerns, and the water runoff was managed carefully in many cities. All of these factors illustrate a sophisticated level of engineering and civic organization.

The Great Bath is interpreted by a variety of scholars and has numerous functions. Some scholars believe it was a ritual tank for people to bathe and purify. Other scholars have suggested that the Great Bath may have been a civic or ceremonial gathering place. Although the original purpose of the Great Bath cannot be determined, the high level of sophisticated technical skill necessary for producing masonry (brick work and bitumen methods would be needed to make the Great Bath waterproof) indicates that the people who built the Great Bath were highly skilled. The lack of a clear point of authority or centre (i.e., priests or kings) in relation to the Great Bath presents challenges for considering the nature of authority and the role of public works in the ancient Harappan civilization.

5) The enigmatic seals and the religious question

The small carved seals made of steatite are one of the most representative artifacts from the Indus Valley civilization. Most of these seals contain images of animals (such as unicorns, bulls, elephants), short sequences of script signs, and occasionally a human or mixed figure. It is likely these seals were employed on trade and administration purposes (pressed into wet clay as a way to mark/disguise goods); however, several of these seals appear to be decorated with symbols or ritualistic motifs.

One well-known instance, also known as the Pashupati seal, shows a figure sitting down and surrounded by animals on either side of them. Some experts view this seal as an early representation of the future development of horned-god and yogic images seen in later South Asian religions, while other scholars caution against assuming that such religious imagery existed earlier than we currently believe it did. The fact that seals could be used for both commerce and religious purposes indicates that much of what we know about the Indus Valley civilization points to multi-faceted uses for objects, meaning that single-use explanations are not sufficient to explain why something was made or what it meant, or how it might have been used.

6. Long-distance trade and the “Meluhha” connection

Products made in the Indus region have been discovered as far away as Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf region, and the Middle Eastern area. Mesopotamian cylinder seals have also been located in the Indus River Valley area. The Indus civilization relied on exports of carnelian beads, faience (a type of ceramic), and copper/bronze objects. Likewise, the imports of tin, silver, and lapis lazuli from this civilization were needed to create many items. In addition, Indus seals discovered in the city during excavations provide strong evidence that trade existed between the Indus region and during this time period, as well as the trade between the two cultures across the Mediterranean Sea.

Although evidence of trade exists for the Indus civilization, many aspects of how trade operated — including merchant organization, credit systems, shipping logistics, and social status of industry participants — are not fully understood due to the lack of commercial documentation from the Indus civilization.

7. Craft specialization: dentistry, metallurgy, beadwork

The Indus peoples were skilled craftsmen and produced a wide range of items. The Indus peoples created beads, faience, glazed pottery, metal (copper and bronze), precious stones, and decorative seals. Additionally, there are archaeological evidence of dental work performed on human remains found at early sites (ex., drilling in the teeth) dating back over 5,500 years in the Indus Valley, making this one of the earliest known forms of dental care in human history.

This raises questions about knowledge transmission and professional organization: how were crafts organized? Were specialized neighborhoods or guilds responsible for particular trades? How did they train apprentices and control quality over generations and across cities?

8. Limited evidence of warfare — an unexpected calm?

In contrast to other ancient civilizations around the world, especially Mesopotamian civilizations, there is very little evidence of massive, large-scale warfare among contemporary settlements in the Indus River Valley due to a lack of fortifications or strongholds, mass graves, layers where cities were destroyed, and extensive amounts of weapon caches. Some settlements have built strong defensive walls, while others have built mounds and fortifications that could be used for either flood protection and administrative purposes; however, combined with the lack of large-scale battle sites in the Indus Valley, we can reasonably conclude that large-scale warfare occurred infrequently, or in some other form, not leaving an archaeological context.

Because the available evidence shows only a minimal amount of evidence from warfare, some scholars theorize that their societies were stable primarily through long-distance trade relationships and/or diplomatic negotiations or other non-violent means for resolving conflicts at local levels. The lack of readable records, however, limits the potential to draw definitive conclusions from the historical evidence and allows for multiple interpretations.

9. Sudden Decline & Disappearance

Around 1900 BCE, many of the major urban centres were beginning to experience decline or change. The cities became smaller, their settlement pattern moved from the Indus Valley to the Ganges River Basin (located further east in India), and many of the artisanal skills established during the Indus Valley era began to disappear. Various theories were developed to explain this process, ranging from simple invasion explanations to more complicated theories encompassing many possible causes.

- Climate and hydrology: Recent research into ancient climatology suggests that there was less intense rainfall from monsoons and changes in how the rivers flowed or where they flowed (the Ghaggar-Hakra/Saraswati system), which created sustained periods of insufficient amounts of water, leading to agricultural failure in specific places. The most recent studies undertaken using both modelling and multiple sediment samples have begun to provide evidence that these extreme dry conditions, coupled with river changes, presented significant stressors across many parts of the country.

- Economic reorientation: Disruptions in trade networks-both in Mesopotamia and elsewhere-could have reduced urban incomes and the capacity to maintain large public works.

- Sociopolitical transformation: Urban elites and institutions may have reorganized or relocated, producing a patchwork of continuity and change rather than a single catastrophic end.

- Environmental degradation and soil salinization: Overuse of irrigation in certain areas may have reduced soil fertility, prompting migration and reduced urban productivity.

Current consensus tends to favor a regionally uneven decline driven by interacting environmental, economic, and social factors, rather than a single violent event.

10. New methods, new evidence — and new questions

The last 20 years of research in the Indus Valley have dramatically increased in scope and knowledge due to new technologies. This includes the use of both satellite imagery and remote sensing to identify previously unidentified archaeological sites, the analysis of isotopic and ancient DNA to understand patterns of movement and diet, and the collection of high-resolution temperature records from paleoclimate cores to establish weather patterns over the long term. Each of these innovative techniques is leading to the development of new information about the chronology of the Indus Valley, and many new questions are being raised as a result. For instance, a genetic study may identify movement patterns for people, but such a study does not indicate language or belief systems, while a remote sensing study may identify the location of a lost city, but only excavation can provide insight into how people lived in those cities.

Why these mysteries matter

The Indus puzzles are of great importance because they challenge our ideas regarding how cities develop and sustain themselves. The technology of this civilisation (urban drainage systems, mass-produced goods, and the long-distance trade of goods) existed alongside forms of social organisation that do not exhibit many overt features of social hierarchy. As such, the Indus Puzzles compel historians to rethink whether our models for understanding cities — based primarily on literate civilizations with well-documented archives — are overly restricted. The Indus demonstrates that complexity can take on many different forms, and that “silence” (the absence of written documents) is itself a historical phenomenon that we must learn to interpret.

Conclusion — An unfinished conversation with the past

The Indus Valley Civilization has both a bright, intellectual future and an obscure past. Its bricks, baths, and seals clearly demonstrate both the sophisticated technology and civic responsibility of its inhabitants. However, because there is no written record and therefore no means to compare the social order to other known civilizations, there is little guidance for historians or civilians as they look to understand the society. Every time an archaeological excavation is conducted, a spectrometer scan is performed, or a satellite image captured, we gain valuable information that will assist in piecing together the history of the Indus Valley Civilization, but at the same time, the potential for new theories on various aspects of this ancient civilization increases as well. The most significant aspect of the Indus Valley Civilization is the combination of accomplishments with unanswered questions. This highlights the fact that not all ancient cultures have yet reached a full understanding of their environments; therefore, new information and future questions need to be considered in conjunction with the current body of knowledge to achieve a greater understanding.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS