Table of Content

Contents

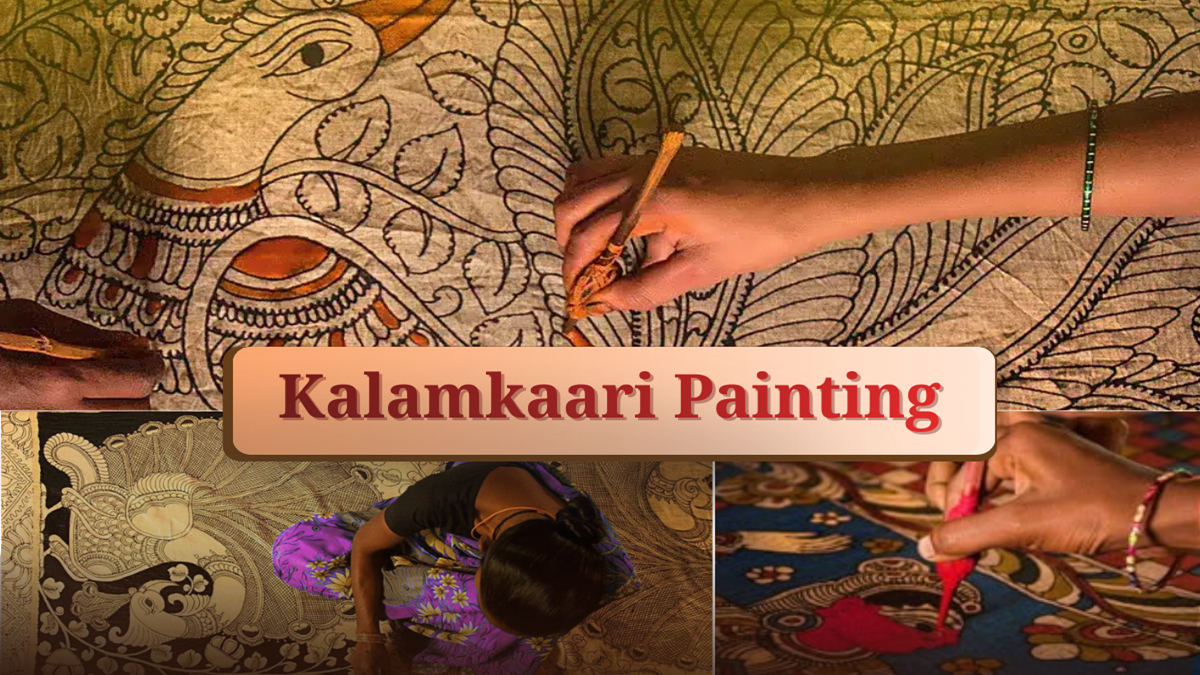

Kalamkari—means “pen work”—is one of India’s most soulful textile traditions. Mostly devotional, occasionally decorative, read-made cloth ignites fromables into vibrant narratives: gods and goddesses, epic scenes, flowering vines, and peacocks painstakingly scripted with natural process. For centuries, Kalamkari artists have told narratives with a simple bamboo (or date-palm) pen, an earthy palette of natural dyes, and the enlivening art of storytelling within religion, historical importance, and craft. This article reflects on the history of Kalamkari; reviews the major styles of the art; unpacks the painstaking process used by the artist to create each piece; explains the major themes and symbolism; and lastly, how the art has thrived and evolved to stay alive in the 21st century.

A living tradition: What is Kalamkari Painting?

Kalamkari Painting is a form of textile art that involves either hand-painting or block-printing and has its origins in the Indian subcontinent. The term is derived from the Persian word kalam (pen) and kari (work); however, Kalamkari Painting was created more directly through local devotional and storytelling traditions. Historically, Kalamkari pieces were made to hang in temples or as storytelling scrolls. Throughout this process, the pieces were created to inform, celebrate, and worship. Today, Kalamkari appears in sarees, stoles, tapestry, housewares, and contemporary fashion – still, the spirit of Kalamkari lives on through its slow manual method and the storytelling power of its imagery.

Historical origins: Roots in Devotion and Trade

Kalamkari Painting is closely tied to the eastern Deccan and, more specifically, to the temple town of Srikalahasti (near Tirupati) in the state of Andhra Pradesh and the port town of Machilipatnam (or Masulipatnam) on the Bay of Bengal. In Srikalahasti, the art emerged as an offering to temples: painters made long narrative scrolls picturing important episodes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas for priests and storytellers to use in ritual and education. Since they were hand-drawn, communities could “read” these sacred stories visually through these experiences.

Machilipatnam became the center of a different, but related practice: textile printing for trade. Block-printed Kalamkari Painting made in Machilipatnam was traded in India and beyond its borders across the Indian Ocean. Persian and Mughal decorative influences, floral vines, stylized borders, and palmette motifs merged with local themes to form a unique commercial textile style.

The art form drew in influences from the patronage of Hindu temples, to the courts of Muslim princes, to European commerce, over the centuries, but in spite of variations between hand-drawn and block-printed, Kalamkari was reliably characterized by its use of natural dyes and handmade techniques.

Two traditions: Srikalahasti and Machilipatnam

Kalamkari Painting today is usually classified into two primary schools, each with its own technique, aesthetic, and social function.

Srikalahasti (Hand-Painted)

- Completely hand-drawn with a bamboo, or date-palm, pen (the “kalam”).

- Focuses on narrative scenes from Hindu epics and Puranic stories.

- Typically take the form of long scrolls (pattachitra-like), panels, or very large temple hangings.

- The style emphasizes fine line work, clarity of narrative storytelling, and rhythmic composition—figures in registers with symbolic and border motifs.

- The manual method of hand-painted Kalamkaris means they are labor intensive, and they are relatively small-batch editions.

Machilipatnam (Block-Printed)

- Employs carved wooden blocks to print designs onto fabric; the next steps involve hand-coloring and block filling.

- Aesthetic influenced by Persian floral vocabulary and the decorative sensibilities of courtly textiles.

- Designed historically for trade and domestic use—curtains, bedding, saris for everyday wear.

- Faster and more adaptable to mass production than fully hand-drawn work.

Both styles rely on natural dyes and traditional mordants; the distinction lies mainly in the tool (kalam vs block) and the intended use (ritual narrative vs commercial textile).

Step-by-step: How Kalamkari is Made

Kalamkari’s process is long and methodical. Below is a distilled step-by-step that highlights why each piece takes time, skill, and patience.

- Preparing the cloth:

The cotton fabric undergoes a wash, soak, and treatment to eliminate starches and impurities. Traditional recipes call for a treatment of the fabric with a combination of cow dung, oil and ash, followed by a soak in myrobalan (a naturally occurring tannin). This assures the cloth has the correct absorbency and has enabled the dye to set properly. - Sketching the design:

In the tradition of hand-drawn, the artist will freehand the figures and compositions using a kalam with tips with iron or carbon-based inks. Usually, the composition regularly follows episodic narratives—several scenes drawn in horizontal bands. - Outlining:

The outlines are drawn carefully, as they provide the structure for coloring in afterwards. The black or dark outline is part of Kalamkari’s visual identity.

- Preparing natural dyes:

The colors are sourced mostly from either plants or minerals: indigo yields blue, madder (or manjistha) yields red, pomegranate rind provides yellow, rust or iron equals black, and alum or myrobalan acts as a mordant. Making dyes is an art—extracting, concentrating, and compounding colors takes deep practice and knowledge.

- Color application:

Colors are layered sequentially, usually from light to dark. There might also be multiple washings and fixings. Finally, the artisans use steady hands and small brushes, or a cup-like instrument to pour pigments inside the outlines.

- Fixing and washing cycles:

After the colour is applied, the fabric is regularly washed to remove excess dye and reveal the ultimate colors. This curing process may also soften hues and unify colors.

- Final touches and embellishments:

After the basic work is done, the artist may add fine details through dotting, crosshatching, and borders that enhance the rhythm and visual density of the piece.

The entire process can take days or weeks, depending on the size and intricacy of the piece.

Colors and materials: An earth-based palette

A defining feature of Kalamkari is its reliance on natural dyes and traditional mordants. These materials lend the textiles an organic, time-softened palette and remarkable durability when cared for properly.

- Indigo (Neel): Extracted from Indigofera species, responsible for deep blues.

- Madder (Manjistha): Yields reds and maroons; often layered to achieve depth.

- Pomegranate rind and turmeric: Provide various shades of yellow.

- Iron and jaggery mixes: Used to create browns and blacks; iron sometimes reacts with tannins to deepen colors.

- Myrobalan (haritaki): A tannin-rich fruit used as a mordant to fix dyes and enhance fastness.

Because these are plant- and mineral-based, Kalamkari colors age gracefully and develop a patina that many collectors prize.

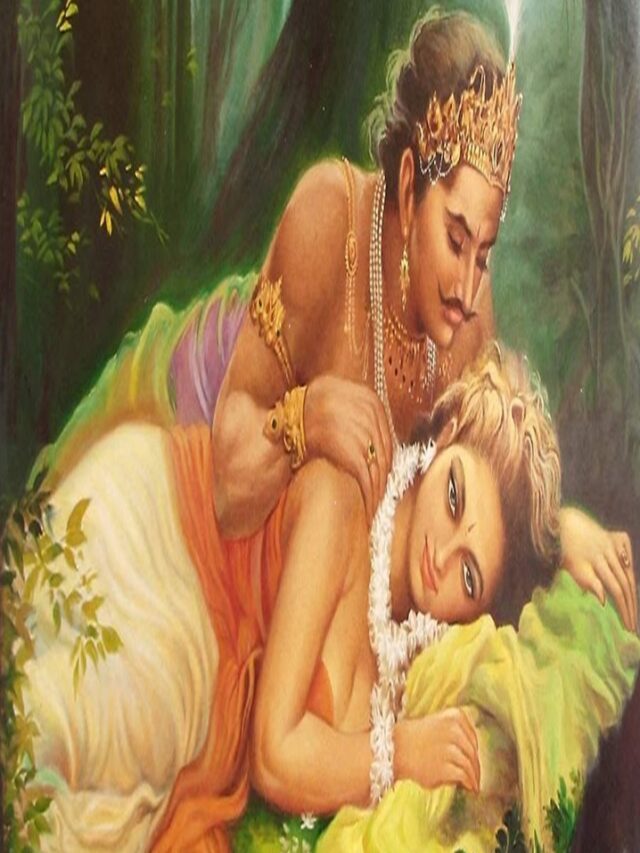

Themes and Motifs in Kalamkari Art

Kalamkari art is rich in symbolic meaning. Whether illustrating an epic or decorating a saree, motifs are chosen with intent.

- Epic narratives: Ramayana and Mahabharata episodes dominate hand-painted Kalamkari. Each scene is composed to tell a part of a larger story.

- Divine figures: Vishnu, Krishna, Rama, Shiva-Parvati, Durga, and local deities frequently appear, often stylized to local iconographic conventions.

- Nature: Lotuses, peacocks, elephants, and mango vines signify fertility, beauty, and auspiciousness.

- Borders and geometric patterns: These frame the narrative and provide compositional balance—repeating motifs evoke continuity and ritual rhythm.

Beyond aesthetics, Kalamkari Painting served as a visual scripture for largely oral communities; painters performed the role of storyteller and custodian of cultural memory.

The Revival and Modern Adaptation

In the past few decades, Kalamkari art saw a profound change. It transcended temple art and traditional dress, influencing fashion, interior design, and contemporary art as well. Contemporary designers and firms adopted the style in sarees, dupattas, furniture upholstery, wall hangings, and now, even footwear.

Government agencies, NGOs, and private establishments have led efforts to revive the craft and sustain it through training, funding, and equitable access to the market for artisans. Design institutions have explored changing some of the original art to modern interpretations, while maintaining fidelity to the original processes.

Digital platforms and e-commerce have provided Kalamkari art with an international audience. Those who are conscious of their consumption now resonate with fashion that is made using sustainable materials, natural dyes, and is handmade—a natural fit with sustainability.

How to recognize authentic Kalamkari

If you’re buying Kalamkari Painting, keep a few authenticators in mind:

- Look for hand-drawn lines: Srikalahasti pieces have irregular, lively lines that machine-made prints can’t copy. Minor asymmetries indicate handwork.

- Check the back: On hand-painted pieces, color saturation and brush marks can be visible on the reverse.

- Natural dye characteristics: Natural dyes often show subtle variations in tone; overly uniform, hyper-saturated colors may indicate chemical dyes.

- Ask about process and provenance: Authentic artisans or cooperatives will describe dye sources, the number of wash cycles, or the village of origin.

- Price and time: True hand-drawn Kalamkari is time-consuming—very low prices can be a red flag for mass-printed imitations.

Supporting certified cooperatives and direct-from-artist purchases ensures fair compensation and craft integrity.

Why Kalamkari matters today

Kalamkari is more than just decorative work; it is a living archive of textile history. Every panel or saree carries techniques, ritual memory, and a community’s signal to fabric knowledge of plants, dyes, and iconography. In a globalized design world, Kalamkari is an example of sustainable craft—made with plant-based dyes, low energy methods, and manual production—compatible with current discourse and concerns around environment and authenticity.

Kalamkari work is income and identity for artisans. It is also a chance to reconnect with storytelling traditions for the audience and support art, crafts, and heritage that stand in opposition to normalizing practices in terms of production, practice, and consequences.

Ways to support Kalamkari artisans

- Buy genuine work from artisan cooperatives, craft melas, or verified online platforms that list the maker.

- Choose quality over quantity: A single hand-painted shawl supports more craft labor than multiple inexpensive printed items.

- Encourage contemporary use: Wear Kalamkari sarees and scarves, use Kalamkari home décor, and accept the craft in modern contexts.

- Learn and share: Host workshops or invite artisans to talk about the process—awareness builds demand.

- Support training programs or NGOs that provide market access, design support, and fair wages.

The pen that writes culture

Kalamkari is not merely a craft; it embodies a dialogue between hand, earth, and narrative. The kalam—the humble pen of bamboo or palm—bridges the artist’s hand to centuries of mythic and quotidian life. Each line painted is a sentence in the longer cultural story. As designers rethink motifs and younger artisans use alternative materials, Kalamkari continues to show that tradition can be rooted and renovated

If you want a piece of India that speaks to a practice of ritual, craft, and resilience, then search for a Kalamkari creation. Within its marks is not only creativity, but a community’s memory, recorded and conveyed patiently, stroke by stroke.

Every Kalamkari is a small history; every penstroke a voice that refuses to be lost.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS