Art is the connection between the heart and the world. It can convey our emotions, our beliefs, and our values. The Pattachitra Painting Scrolls of Odisha and West Bengal represent one of the finest Indian art traditions that do this. These artworks originated in religious ceremonies and folk theatre; hence, they function as sacred texts as well as present-day storybooks. The Pattachitra scrolls display the many stories, deities, and the rich visual culture of eastern India. The following article will give an overview of the development of Pattachitra painting, the materials used, the techniques employed, the themes explored, the function and evolution of the Pattachitra painting scrolls today, and the steps required to maintain this art tradition into the future.

What is Pattachitra? More than Paint on Cloth

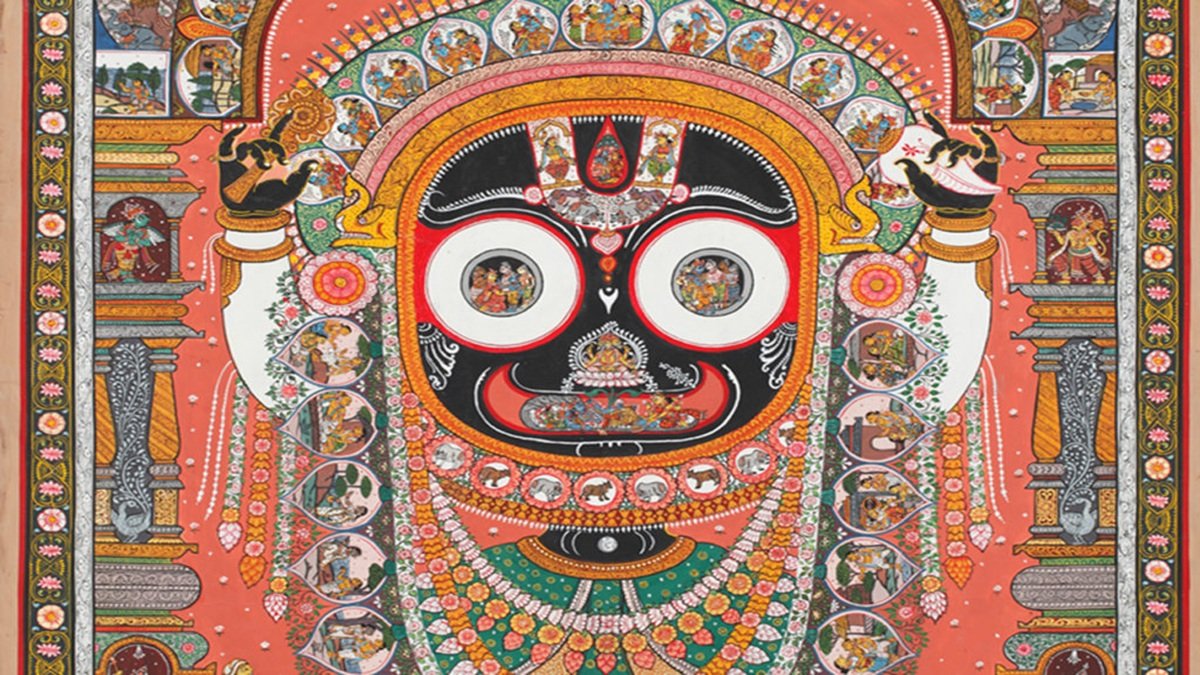

The term Pattachitra comes from Sanskrit: patta (cloth) + chitra (picture). The name is somewhat of a disservice to how rich this artistic medium is in spirituality (and therefore how powerful of a story it can tell). As a form of storytelling and worship, the Pattachitra takes the form of scrolls (painted) depicting scenes from the Bhagavata Purana (one of the main texts in Hinduism), Krishna’s life, the Ramayana and Mahabharata (major texts of Hinduism), and local folklore. In Odisha state, the Pattachitra is closely associated with Jagannath worship, while in the Bengal region of eastern India, it is part of the tradition of itinerant performers and village life. Whether it is displayed in a shrine or unrolled for storytelling, the Pattachitra acts like a visual scripture; it can be taken anywhere, and it can be used as an object of communal worship.

Historical Roots: From Temple Courtyards to Village Squares

It is difficult to determine the exact origins of Pattachitra, but its development can be traced back to the emergence of temple culture in eastern India. The people of eastern India have always been artisans, and during the medieval period, the towns of Odisha’s temples served as major centers of production for a variety of crafts. The Jagannath cult, which developed in the city of Puri, created a rich tradition of pictorial devotion. Families of local Chitrakars (artists) created both scrolls and paintings that supplemented the rituals performed at the temples; thus, the development of the art and the calendar of festivals influenced one another significantly.

During this time, another tradition developed in Bengal that paralleled the tradition of Odisha. In this instance, Pattachitra paintings evolved into a new art form called Patua, which was practiced by itinerant painter-singers. The Patua travelled from place to place, singing or chanting to create a story using musical, written, and pictorial elements. Through this storytelling format, they could engage and educate audiences in rural areas. As a result of these differences, the styles of these two forms have changed significantly. However, both Odisha and Bengal have maintained a strong commitment to narrative art forms.

Two Traditions, One Soul: Comparing Odisha and Bengal Styles

Although the two traditions share a name and many techniques, their visual languages and social roles are distinctive.

Odisha Pattachitra

- Centers: Raghurajpur, Puri, and the surrounding Chitrakar villages.

- Character: Highly stylized religious imagery, bold black outlines, flattened perspective, dense ornamental borders.

- Themes: Strong focus on Jagannath, Krishna leelas, Dashavatara, scenes tied to temple rituals.

- Function: Objects of worship, temple offerings, and devotional gifts.

Bengal Pattachitra

- Centers: Birbhum, Medinipur, Bankura, and rural clusters where Patuas live.

- Character: Narrative sequencing, panel-by-panel storytelling, a closer relationship between text and image.

- Themes: Mythology as well as social commentaries, local legends, moral stories, seasonal and life-cycle narratives.

- Function: Performed storytelling, community entertainment, and educational tools.

Both traditions are performative in spirit: one within ritual frames, the other in the marketplace and village square. Together, they show how the same art form can adapt to different cultural ecologies.

Materials & Techniques: Handmade from the Ground Up

Pattachitra’s power comes from its craft — every painting is the result of careful, mostly natural methods that have been handed down across generations.

Preparing the patta (cloth):

Through a systematic process, a piece of cotton transforms from a simple piece into an investment-grade surface for a painting. The cotton is then coated with a combination of chalk (or ground stone) and natural gum and is sanded and polished to even out the surface and provide an absorbent area to work with. One of the benefits of this process is that it helps colours stay in place, and the paint typically has a matte finish that resembles a jewel-like quality.

Natural pigments

Traditional Pattachitra uses pigments made from minerals, shells, plants, and soot.

Examples include:

- Whites from conch powder,

- Reds and ochres from natural earth pigments,

- Blacks from lamp soot or charcoal,

- Blues and greens from mineral blends or plant dyes.

These pigments are bound with organic gums or resins. The result is a color that ages gracefully and carries a distinctive, earthy luminosity.

Brushes and strokes

Artists use animal hair, squirrel tails, or plant fibres to create fine brushes with precision in their craft. These artists produce flat areas of colour framed by thick, straight outlines, while they also design decorative borders and complex designs with tiny, precise strokes. Thus, there is a focus on the use of line, pattern, and rhythm on the painted surface rather than creating the illusion of depth.

Sacred Stories: Themes, Iconography & Symbolism

Pattachitra is essentially storytelling. Each scroll is an unbroken narrative (and therefore has chapters), which the interpreter views from left to right—that is, panel by panel.

Major mythological themes:

Krishna leelas: Childhood mischief, the butter-theft episodes, the Rasa Lila — these scenes are rendered with emotive faces, rhythmic composition, and symbolic accoutrements (peacock feathers, flutes).

Jagannath narratives: Odisha’s paintings often center on the Jagannath triad — Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra — and events from the temple calendar.

Ramayana & Mahabharata: Heroic episodes and moral dilemmas are common subject matter.

Folk and social narratives

Artists use animal hair, squirrel tails, or plant fibres to create fine brushes with precision in their craft. These artists produce flat areas of colour framed by thick, straight outlines, while they also design decorative borders and complex designs with tiny, precise strokes. Thus, there is a focus on the use of line, pattern, and rhythm on the painted surface rather than creating the illusion of depth.

Symbolism

Colors and motifs within these works have a cultivated message: lotuses represent purity; conches represent sacred sound; borders may contain floral, geometric, and animal images, and all patterns have further meanings. The format of the piece—the positioning of the figures—illustrates the way that the two-dimensional surface conveys hierarchies within a narrative.

Role in Religious & Social Life

Pattachitra functions in a dual capacity, both as an object of worship in temples and as an object of art within the home. In the state of Odisha, both types utilize hand-painted paintings created by artisans. A patta is considered to be a devotional offering to a god, but it can also represent the text of religious teachings (as with a pasarr) and an illustration of the lives and experiences of those who perform worship.

The Bengal Patua tradition takes more of a public approach to sharing its art. Story singers regularly perform at fairs, weddings, and festivals. The visual element of the patua is used both as a performance element and as a method for teaching; thus the patua serves as a means for collective memory and retention within communities that lack a high level of literacy. The patua enhances the understanding of local cosmology, local history, and ethical teachings.

Across both regions, Pattachitra strengthens communal identity: it is a craft that ties families, villages, and faith communities together.

Decline, Revival & Recognition

Many traditional artisanal crafts, such as Pattachitra, suffered greatly because of the introduction of mass-produced items, as well as from the decline in agriculture due to the advent of a technology-based economy. As a result of these two factors, there has been a steady decline in the sale of handmade items. Additionally, the younger generation is no longer interested in pursuing artistic professions and prefers other careers.

While the story of decline is prevalent, there is also an ongoing story of revival. Many groups are working to revive training opportunities, establish craft centres, and create connections to markets. With more people visiting and tourists coming to see their work, many craftspeople are earning good incomes from exhibiting their products. Many craftspeople have also embraced modern media by trying out new techniques and product designs in addition to the traditional methods they learned in the beginning.

Reviving the market requires more than market access; it also requires structural assistance for this to continue, such as fair pricing policies, as well as design partnerships that respect the art form’s traditions and the type of education that combines the heritage of the craft with the economic realities of the modern marketplace.

Pattachitra in Contemporary Life: Adaptation and Innovation

Pattachitra has changed in order to survive. Pattachitra artists paint on many different kinds of surfaces, such as framed boards, decorative panels, fabric items, and modern-day canvases. They are now collaborating with designers to produce home décor, clothing, and accessories, and small-sized works for people’s modern lifestyles. Digital platforms (through social media and online stores) have allowed Pattachitra artists to reach a wider audience internationally and to share the story of their work.

Simultaneously, when considering innovation, there arise issues regarding preserving the soul of Pattachitra through innovation arise. A number of artists have responded to this question by continuing to use traditional techniques, but additionally develop new thematic ideas and products – an approach that allows them to show respect for their ancestors while also having access to new means to earn an income.

Challenges & Paths to Sustainability

Key challenges remain:

- Economic vulnerability: Many practitioners still earn modest incomes compared to the cultural value of their work.

- Transmission of craft: Younger people often pursue alternative careers; sustained apprenticeship programs are needed.

- Authenticity vs. market taste: Pressure to cater to tourists or mass markets can dilute traditional forms.

Addressing these requires multi-pronged efforts:

- Creating fair-trade supply chains and direct-to-consumer platforms so artists capture a larger share of value.

- Investing in community-based training and youth engagement that makes craft a viable career choice.

- Encouraging ethical collaborations with designers and institutions that respect technique and narrative content

- Supporting documentation, museum partnerships, and educational programs that keep the iconography and stories alive.

Why Pattachitra Matters

Pattachitra is Relevant on several fronts. The aesthetic qualities of Pattachitra include line, colour, and pattern in the creation of decorative images that convey deep meanings. Additionally, Pattachitra serves as a visual archival record of cultural histories (historical events, cultural traditions, etc.). It also embodies the culture through various social means (e.g., craft lineage; performer communities) where the livelihood and identities of the artists are dependent on their practice of Pattachitra. Finally, Pattachitra can act as a medium of devotion through its ability to create communal experiences around the appreciation of visual beauty.

When a child watches a Patua singer or a family brings a painted panel into their home, they are not only seeing art — they are participating in a chain of memory and meaning.

Protecting a Living, Sacred Art

Rather than being an object to be displayed in museums as artifacts, Pattachitra should be viewed as an ongoing process of creation and continuity that needs to be encouraged through support for market access, training opportunities and by encouraging a fair wage for the artisans who produce Pattachitra as well as maintaining a cultural commitment to honouring the sacred origins of the craft, respecting what artisans can teach us, and developing the capacity to appreciate the inherent value of handmade crafts without requiring any justification or validation.

For readers and culture lovers alike, Pattachitra gives you a gentle nudge in the direction of looking more closely at the line being drawn, listening to the song behind the scroll, and thinking about how images can transmit story and spirit across time. In an age where speedy and disposable products are valued over other things, Pattachitra’s slow brushwork provides an opportunity to create another rhythm — a rhythm that allows for the collaboration of devotion, narrative, and human hands, all working together to create something meaningful.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS