Table of Content

Contents

When a clay lamp first illuminates the window and as incense wafts throughout the family’s courtyard while they fry laddu, it is at times a celebration of something much older than any one celebration. Deepavali (Diwali), like many festivals around India, possesses myriad local customs, lore, household traditions, and community celebrations, but fundamentally represents the triumph of Light over Darkness, Renewal over Decay, and Collectivism over Individualism, even though the customs and expectations may vary across languages and regions in the various states of India.

Deepavali was recognized as a formal International celebration in December 2025 when it was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The listing of Deepavali acknowledges that it is not only religious in nature but also continues to be a vibrant Cultural Practitioner of Family and Community Values: a means through which Social Values are passed from generation to generation.

This article traces why Deepavali matters: its meanings, its many sacred strands, its regional colours, and the ways in which this long-lived tradition is being cared for — and reinvented — in a modern world.

The Meaning of Deepavali: Light Over Darkness

The word Deepavali has its origins in the Sanskrit language, consisting of two parts – ‘Deepa’ meaning ‘lamp’, and ‘Avali’, meaning ‘row’. The combination of these two terms essentially means ‘a row of lamps’, which is one of the earliest images associated with this celebration. Deepawali also has many other symbolic meanings associated with the festival; for example, the lamps represent both moral and intellectual enlightenment, or light. The rangoli decorations at the entrance to homes symbolize hospitality and prosperity, and the exchange of sweets and gifts represents the community aspect of the festival.

The flexibility of the symbolic core allows everyone to incorporate many meanings into one festival. For one family, Deepavali could be a time to honour their ancestor(s); for another family, it could be a time to commemorate their fiscal new year; while many may see this as an opportunity to pray for prosperity, or, at the same time, celebrate their own spiritual liberation. The fact that it has this degree of elasticity allows Deepavali to continue to exist as ‘living heritage’, not simply a fixed ritual.

Mythological Roots Across India

Deepawali’s “why” is not a single story but a chorus of local and scriptural memories. These narratives often coexist — told sometimes in the same home — and they help explain why the festival is felt so widely.

- The Ramayana tradition: In Northern India, the best-known account of Deepavali is associated with Lord Rama’s homecoming to Ayodhya after 14 years in exile and his triumph over the demon Ravana. Lighting lamps to welcome Lord Rama back to Ayodhya is a tradition of many Northern Indian cultures and today serves as the basis for Northern Indian celebrations of Diwali.

- Krishna and Narakasura: In parts of the South, Deepavali is connected with Krishna’s defeat of the demon Narakasura; here, early-morning rituals and oil baths mark the day.

- Lakshmi Puja and commerce: Deepavali is considered a festival for many merchant communities who honour the goddess of wealth and prosperity (Lakshmi). For merchants, it is the final day to close their books for the previous year and the first day to begin keeping their books for the new year, through a ritual known as Chopda Pujan or Business Puja.

- Jain and Buddhist linkages: Jain communities observe Diwali as the day when Mahavira attained nirvana; in some Buddhist communities, similar commemorations appear.

- Sikh memory: Bandi Chhor Divas: The festival of Bandi Chhor Divas, as it pertains to Sikhs for the liberation of Guru Har Gobind from prison (as well as the liberation of 52 other princes), also overlaps with Diwali historically. This is why the celebration includes the illumination of Gurdwaras and public celebration.

These multiple narratives are not contradictory; rather, they are complementary. These narratives allow different cultures to share their sacred histories at the same time of year. This multiplicity of narratives/festivals (pluralism) is what makes them strong cultural practices.

Deepavali as a Pan-Indian Cultural Celebration

The uniqueness of Deepawali as a cultural event lies in its role as a collective cultural memory. As well as being a festival celebrated by Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, and some Buddhists; it is a culture shared by much of the Indian population, regardless of their religious observance. A major event in the calendar year, for all Indians in India, it marks a time when schools close, stores illuminate their lights, cooking takes place around the home, and families travel home for the holiday.

As a social technology, the shared rhythm of Deepavali regulates the calendar (seasonal, business) and transfers cultural and familial values (charitable, forgiving, hospitable) while supporting social connections through family gatherings/neighbourly visits. The designation by UNESCO stands to reinforce this point about Deepavali being a social practice that creates a sense of belonging; support for livelihoods (both through diyas and sweets); and the expression of intangible knowledge.

Regional Forms of Deepavali

If the festival is a single river, the tributaries are the regional practices that make it visible. A quick sweep across the map shows how local customs add texture:

- North India. Elaborate lighting of courtyards, enactments of the Ramayana (Ramlila), and community fireworks have long characterised northern celebrations.

- South India. Many regions mark the day with pre-dawn oil baths, new clothes, and feasts — and stories of Krishna and Narakasura are prominent.

- West India (Gujarat, Maharashtra). Here, Deepavali often marks a business new year; merchants perform Chopda Pujan and exchange sweets and good wishes.

- East India (West Bengal, Odisha). In Kolkata and parts of Bengal, Deepavali’s energetic counterpart is Kali Puja — a night-long worship for the goddess Kali that shares the calendars and a spirit of luminous ritual.

- Northeast and tribal regions. These areas adapt the festival to local seasons and social structures, making Deepawali part of a broader cycle of harvest and community celebration.

These regional forms show the festival’s capacity to be local without losing its national identity — a key trait of living heritage.

Rituals That Carry Cultural Wisdom

Many Deepavali practices look simple but carry social knowledge:

- Cleaning the house. A ritual sweep becomes a moral metaphor: purify the home to receive fortune and clarity.

- Lighting lamps and candles. The act of lighting is a communal, visible commitment to dispel fear and raise hope.

- Rangoli and decoration. Floor designs are cosmetic and protective — a boundary art that invites guests while honouring thresholds.

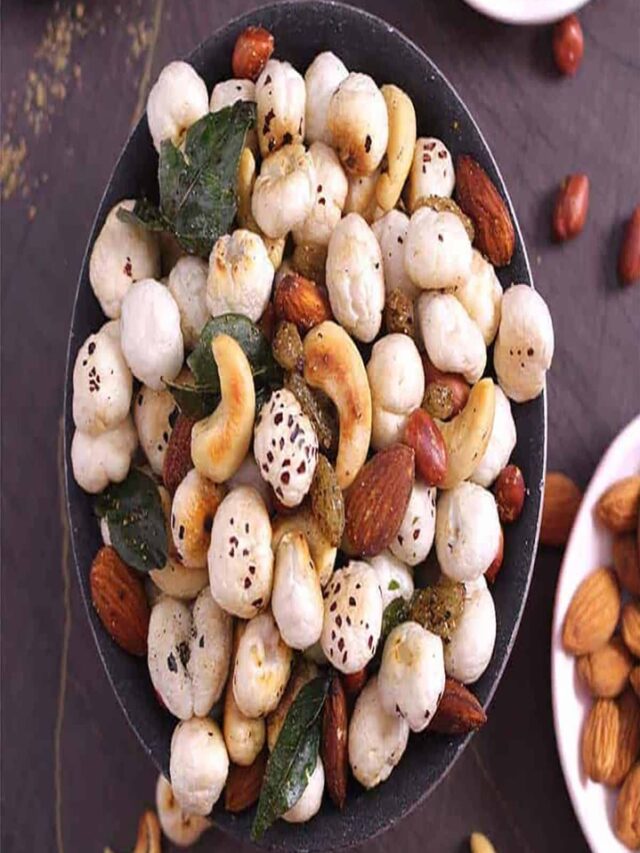

- Sweets, gifts and feasting. Sharing food is not only hospitality but a mechanism for reciprocity and social bonding.

- Public prayers and communal meals. Whether in temples, gurudwaras or community centres, the festival reshapes private piety into public celebration.

Each ritual doubles as pedagogy: children watch elders perform rites; neighbours exchange greetings; values are transmitted by repetition and taste.

Recognition as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

When UNESCO inscribed Deepavali on its Representative List, it did so primarily to protect its ongoing practice, as opposed to simply commemorating a popular festival. By recognising how Deepawali promotes and preserves both intergenerational transmission of cultural values, community involvement in ritual practice, and the intangible arts associated with these traditions (eg, lamp construction, Rangoli, sweet production) that are still used to support people’s livelihoods and cultural identity. This decision, made during UNESCO’s 20th Session of its Intergovernmental Committee, was widely published in the Indian news media and regarded as a significant achievement in India’s cultural diplomacy by many cultural institutions and officials.

The purpose of a UNESCO listing is not to preserve a tradition, but rather to assure that the community is involved in protecting the tradition through measures such as documenting the tradition, providing support to craftsmen, education, and raising awareness about the tradition. The UNESCO listing gives both an honour and an obligation to the festival organisers to maintain the festival as alive, inclusive, and ecologically sustainable.

Deepavali beyond India

People celebrate Deepavali by travelling around the world. Deepavali celebrations have found their way into the cultural calendars of many Southeast Asian countries, as well as Nepal, Sri Lanka, and major metropolitan areas, including Singapore, London, Toronto, and Sydney – all cities that have large populations of Indian immigrants. In addition to promoting Indian culture, Deepavali and the celebration of Hindu festivals offer many people who may not be familiar with them the opportunity to see them as opportunities for public expression and celebration of civic identity through the lenses of illuminated streets, cultural performances, food, and the like. News outlets serving diaspora communities have highlighted the inscription of Deepawali on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity and highlight this event as a proud achievement for increased cultural visibility.

That global footprint also means custodianship: diaspora communities often lead preservation projects (funding artisans, supporting temple restorations, teaching children traditional dances) that feed back into India’s cultural ecology.

Keeping Deepavali alive: Care, Critique and Continuity

A living heritage requires attention on three fronts:

- Community engagement: Safeguarding must be led by communities who practise the festival, including small producers (lamp-makers, sweet-makers, rangoli artists) whose skills deserve recognition and support.

- Responsible celebration: Environmental and safety concerns require continuing conversation and practical alternatives so the festival remains joyful but not harmful. Government campaigns and NGOs have already promoted “Green Diwali” efforts and raised awareness.

- Creative transmission: Schools, cultural programmes, and digital archives help younger generations learn rituals in ways that are meaningful, not merely performative.

These measures keep the festival dynamic — not fossilised — and ensure that the ritual meanings remain legible for new generations.

A Living Heritage That Still Lights the Way

While Deepavali may be a personal and collective celebration that is at the same time a local and a national event, it has also been around for centuries and is being redefined. The simplicity of Deepavali lies in its many symbols (such as lamps, sweets, stories, and being together), which have allowed Deepavali to take on many meanings throughout history, provide livelihoods to many, and travel to places very far away. Deepavali’s recent inclusion on the UNESCO list is simply a modern enhancement of this ancient festival — this recognition reminds us that festivals should not just be seen as entertainment; they are active stores of significance, craftsmanship, and human interaction.

As long as people gather — in small courtyards or wide public squares, in ancestral homes or apartment terraces — to light a diya, share a sweet and tell a story, Deepavali will continue to be more than a festival. It will remain a way a society remembers itself: a living, breathing tradition that turns individual evenings into a shared chorus of light.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS/