Table of Content

Contents

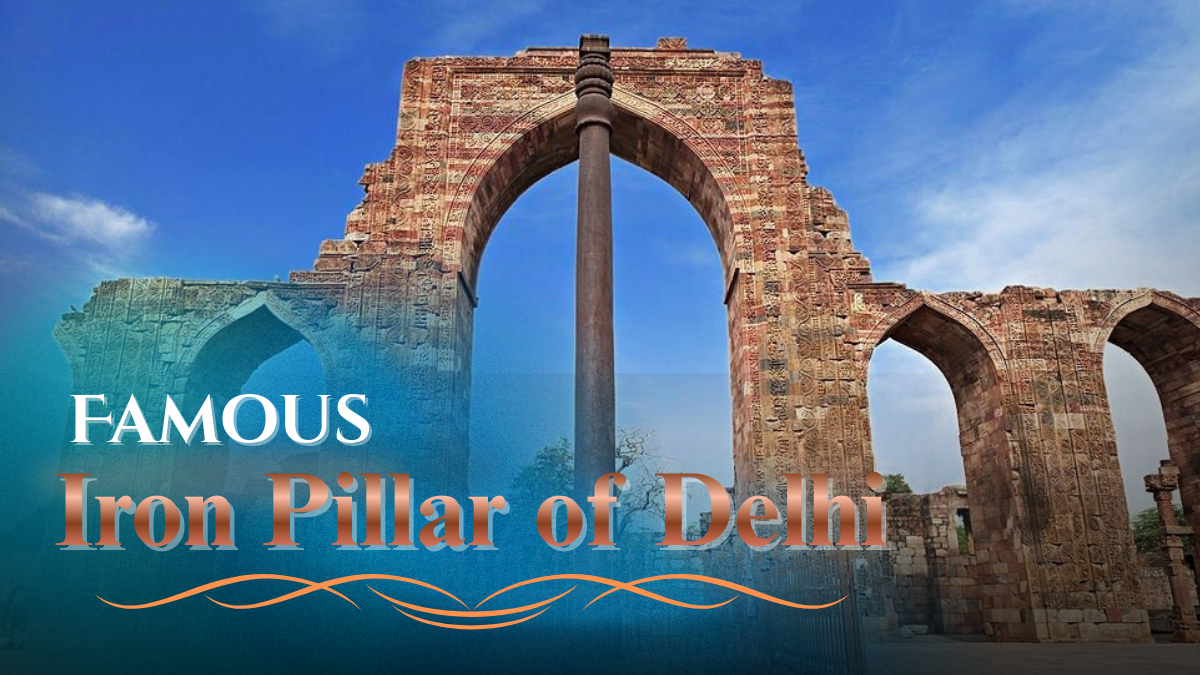

The centuries-old Iron Pillar of Delhi, located adjacent to the Qutub Minar, is considered one of the greatest achievements in ancient engineering and metalworking, due to the tremendous technical skill employed in its construction, as well as the exceptional qualities of iron exhibited by this object. The Iron Pillar represents the integration of science and technology (particularly metallurgy) in the construction of a structure that has remained virtually rust-free despite being subject to the effects of humidity, pollution, and other environmental factors for over 1,600 years, which has fascinated scientists and historians alike for as long as it has existed.

History and Inscription: A Pillar from the Gupta age

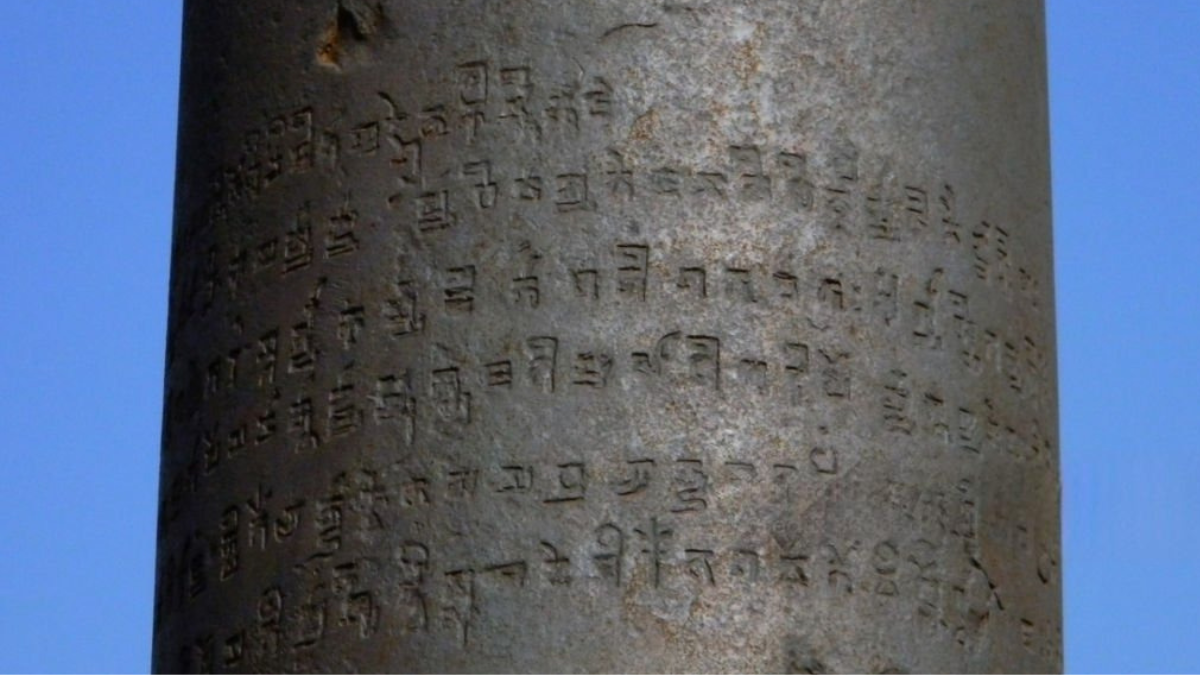

The inscription on top of the pillar is a Sanskrit eulogy that many scholars believe was engraved by the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II (c. 375-415 CE). They came to this conclusion due to the design of the script on the pillar and the type of characters used (paleography). The inscription praises a king “Candra,” who most people assume is Chandragupta II, and describes the column as being dedicated to Vishnu as a dhvaja (flag or standard), located on a hill called Viṣṇupada. The document shows characteristics associated with epigraphy and literary metres common in the late fourth to early fifth centuries; therefore, it is typically placed within the Gupta timeframe.

The inscription’s etched text offers an interesting perspective into courtly language and religious beliefs in ancient times, and it is noteworthy that the text is still very clear on the surface of the iron, thus allowing us to conclude that the surface of the iron plate was also preserved for an unusually long time.

Where it stands — Journey into the Qutb complex

Today, the Iron Pillar of delhi rises within the ruins that surround the Qutb Minar at Mehrauli in southern Delhi, a UNESCO-acclaimed heritage area visited by thousands each day. How the pillar arrived at this site remains uncertain: some scholars believe it was originally erected elsewhere—possibly in Udayagiri or a nearby royal complex—and later relocated to Mehrauli by subsequent rulers who incorporated it into the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque precinct.

Over the centuries, the pillar is also believed to have been moved more than once. One common tradition suggests that during the rule of the Delhi-era Tomara king Anangapala (circa 11th century), it was transported to Delhi and re-erected there. Whatever its exact journey, its presence at Qutb has made it one of the city’s defining curiosities.

Physical & Architectural Features

Understanding the pillar’s dimensions and structure helps appreciate the magnitude of the craft involved:

- Total height: ~ 7.21 metres (around 23 ft 8 in).

- Of this, a portion (about 1.1 metres) is below ground level.

- The visible shaft stands on a stone platform added much later.

- Diameter: At the base ~ 42 cm (16.7 in), tapering to ~ 30 cm (11.8–12 in) just below the decorative capital.

- Weight: Over six tonnes (some estimates ~6.1 tonnes / ~6,096 kg).

- The top of the pillar once likely bore a statue — possibly of Garuda, the mythological bird-vahana of Vishnu. The bell-shaped capital suggests such, though that element is now missing.

The craftsmanship is impressive. The pillar was created with 100% handmade techniques (forge welding, hammering) without machine assistance. Despite this obvious “handmade” quality, there is an absence of joint lines or welded seams apparent on the exterior surface of the pillar. The cylindrical taper and overall design (like clean inscription) were obviously made intentionally, providing precision and functional utility; significantly beyond the plausible craftsmanship level at that time in history!

The Mystery: Why Hasn’t the Pillar Rusted?

The pillar possesses a remarkable resistance to corrosion and oxidation in comparison to ordinary iron exposed to the elements in polluted and humid urban environments. All other ordinary irons corrode relatively quickly, whereas the Iron Pillar has retained most of its metallic surface despite nearly 1,600 years of exposure to the elements. This leads to the question of why this specific piece of iron exhibits such extraordinary resistance to corrosion.

In recent decades, metallurgists have been investigating the microstructure and chemical composition of the Iron Pillar. From meticulous scientific investigation, there is a broad consensus concerning the fact that the corrosion and oxidation resistance of the Iron Pillar of delhi is not an example of the work of supernatural forces, but rather due to the materials used in producing the Iron Pillar, its mode of preparation, and the properties of the thin layer of surface corrosion products that formed over the course of the years.

- The wrought iron from which the pillar was constructed contains an unusually high amount of phosphorus but very low sulfur and manganese compared with typical modern wrought irons, and

- On the pillar’s surface, there is a thin, adherent, protective layer-mostly phosphate-rich-whose crystalline structure inhibits the electrochemical processes that normally drive rusting.

More specifically, detailed analyses (including those led by researcher R.Balasubramaniam and collaborators) describe a passive film composed of iron oxyhydroxides and iron phosphates. This film formed slowly and naturally due to the pillar’s chemistry and the repeated cycles of humidity, dust, and light over centuries. The presence of dispersed slag inclusions and the particular microstructure created during ancient forging also helped create conditions in which protective phosphate layers could nucleate and remain stable.

How ancient smiths made a modern miracle

The manufacturing techniques used to construct the pillar are older than modern blast furnace production of steel and are likely to have been created by ancient craftspeople utilizing the bloomery or charcoal-fired furnace processes. After producing a porous mass of iron (bloom), these ancient craftsmen consolidated it through hammering. By forge-welding layers of wrought iron “cakes” together and continually hammering them into a single shaft, they were able to create a uniformly consistent sectional piece. The hammering process dispersed the slag within the iron and maintained the residual phosphorus in the steel, as phosphorus was plentiful in certain ores when smelted with charcoal processes. The resulting microstructure has an effect on how well the pillar corroded.

Current researchers note that the specific methods (“forging”) that were employed in historic times prevented the removal of phosphorus from iron by high temperature melting, and, thus, phosphorus was retained in the iron. Under certain environmental settings, iron-containing phosphorus can undergo the formation of phosphate compounds on the surface, providing a corrosion preventative surface layer. What may seem to us as “primitive” techniques for smithing today have produced a material very well suited to preservation over long periods of time.

Myths, Legends, and the Crowd at the Pillar

No wonder stories grew up around the Iron Pillar of delhi. Folk tales credit it with magical qualities, and a popular challenge once held that someone could prove their modesty by inserting their hand into a hole at the pillar’s base — a dare that over generations produced many entertaining anecdotes and, in some versions, even physical damage to the immediate base area. These legends, while delightful, are dwarfed by the very real science behind the pillar’s endurance. The mixture of myth and material fact is itself part of the pillar’s cultural appeal.

Conservation and modern studies

Due to the importance of the Iron Pillar at mehrauli as an archaeological finding, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), along with numerous researchers, continues to monitor its state. Current non-destructive techniques (ultrasound, spectroscopy, and more focused metallurgical sampling) have assisted conservators in determining the best means to preserve the pillar and its associated inscribed text. Most researchers have agreed on the pillar’s general characteristics, but they have differing interpretations of the specifics on how and where it was originally erected; how the containers that held its elements were manufactured; and the processes involved in creating the anti-corrosive coating that drastically reduced the corrosion rate of the pillar.

The Iron Pillar in Global Context

While many other ancient iron artifacts exist today in very good condition, the size, age, and clarity of the inscriptions on the Delhi pillar convey how advanced Indian technology was in many fields — including literature, mathematics, and architecture — but also within the field of metallurgy. The pillar is evidence of a different technological reasoning than high-temperature metallurgy, which was predominant in the Industrial Age; the pillar was created using techniques passed down through generations of smiths and passed down through empirical knowledge.

Quick Facts That Amaze Visitors

- Date & patron: Widely attributed to the Gupta king Chandragupta II (c. 375–415 CE).

- Location: Qutb complex, Mehrauli, Delhi (relocated there at some point in later centuries).

- Height: Approximately 7.2 metres (total); weighs several tonnes.

- Material trait: High-phosphorus wrought iron with a stable phosphate-rich passive film that greatly slows corrosion.

Why the Pillar still matters

The Iron Pillar of delhi is not just something to look at on your next trip. It shows the relationship between art and devotion, crafts with science. In the past, artisans created things like the Iron Pillar while at the same time writing religious texts (like the Vedas) and worshipping gods in courts. This happened because there were many skilled craftsmen who worked with both metal and wood using the same tools to gather knowledge about how to create objects; they created amazing items, many of which modern science continues to study. When you stand beneath the Maratha period arch or in front of the ruins of the mosque’s colonnade, you can see how the Iron Pillar at Mehrauli , which has never rusted, serves as a challenge to all creators and inventors. The techniques and crafts that great craftsmen used may be very simple, while it takes long hours of dedication and hard work to develop and create sophisticated items that are still relevant today.

For anyone interested in history, material culture, or the history of technology, the Iron Pillar invites a humble but thrilling lesson: look closely at old things — they often have long, surprising stories to tell.

Subscribe Our YouTube Channel : https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS