Table of Content

Contents

National symbols solidify a nation’s identity: they embody values, recall heritage, and provide a focal rallying point for collective pride. Of its set of symbols, the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) holds a place of honor as the official animal of India. Beyond striking physical presence, it represents an important object of the country’s natural wealth and cultural imagination. In April 1973, the Bengal tiger was formally adopted as the National Animal of India, in part to supplant the lion as part of a new prioritization of conservation needs. The Bengal tiger observed its first designated in 1972, presented by the Indian Board for Wildlife, and soon afterwards initiated the landmark Project Tiger to address the dramatic decline of tigers in India. This article addresses the historical designation of the tiger, its symbolic meaning, its biological and ecological significance, its journey of conservation, its contemporary impediments, and the broader responsibility of representation with respect to the tiger as a national symbol.

Historical Background

In the early 1970s, India officially recognized the Royal Bengal Tiger as its National Animal of India (though accounts vary; some sources mention 18 November 1972), following the Asiatic Lion. The widespread presence of tigers, the ecological importance placed on the tiger, and its deep cultural importance position it as a more appropriate national representative of the nation’s natural history. Historically, tigers occupied the majority of the subcontinent’s forests; tigers appeared on ancient coins, were depicted in Mughal painting, and populated folklore. But centuries of hunting, poaching, and habitat destruction reduced the species to near extirpation, leading India to direct its national interest toward tiger conservation. Because population levels were severely depressed, on 1 April 1973, the Government of India initiated Project Tiger — a landmark, centrally funded conservation program that emphasized habitat conservation, anti-poaching, and continued monitoring. These efforts were later endorsed by the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, the primary statute to provide statutory protection to tigers and other wildlife in India.

Why this is important: granting official status to the tiger made it a national conservation priority, mobilized funding, support and public interest, and provided the legal foundation for the tiger reserve/enforcement regime networks that support conservation in India.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Clade: Synapsida

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Carnivora

- Family: Felidae

- Genus: Panthera

- Species: Panthera tigris

- Subspecies: Panthera tigris tigri

Physical characteristics and adaptations

The Royal Bengal Tiger is the largest member of the feline family and one of the most impressive predators in nature. Adult males usually weigh between 180-300 kg and are about 3 meters from nose to tail, while females are smaller and weigh around 100-160 kg and are about 2.6 m long, though a few have weighed or measured more than that.

Its unique coat — a reddish-orange deep color streaked with strong black vertical stripes — is not only beautiful but also camouflage in dappled woodland light. White on the underside and inside limbs, contrasting sharply with dark flanks, gives it the look of a burning flame in the green forest. Every tiger’s stripe pattern is different, as with a human fingerprint, so scientists can identify individuals with camera traps.

The adaptations of the tiger have made it the top predator of its environment. Its powerful body, strong forelimbs, retractable claws, and short, dagger-like canines are all designed for ambush and short, explosive sprints. Tigers also have good night vision, acute hearing, and smell. Unlike the other big cats, they are good swimmers — they have been known to swim across rivers, and even hunt in rivers, especially in the Sundarbans mangrove.

Geographic Distribution in India

Once ranging over nearly all of Asia, the Bengal tiger’s stronghold today is in India, where they have the largest surviving population of this species. Bengal tigers occur mainly in India, which has almost 75% of the world’s tiger population — an estimated 3,682 in 2025 in just the thirty-one states in India. Their habitats include an incredible array of ecosystems ranging from tropical rainforests and moist and dry deciduous forests to open grasslands and tidal mangrove swamps of the Sundarbans. Their wide ecological distribution demonstrates the tiger’s adaptability and reinforces India’s importance in the global survival of this remarkable predator.

Major tiger landscapes include:

- Central India: Madhya Pradesh (home to Kanha, Bandhavgarh, Pench, and Satpura Reserves) holds the highest number of tigers in the country.

- The Western Ghats: States like Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu sustain large populations in reserves such as Bandipur, Nagarhole, and Periyar.

- The Himalayan and Terai regions: Corbett and Rajaji in Uttarakhand, and Dudhwa and Pilibhit in Uttar Pradesh, form crucial northern habitats.

- Eastern India and the Sundarbans: West Bengal’s Sundarbans, the world’s sole mangrove habitat of tigers, is home to a distinctive population of Bengal tigers uniquely suited to its tidal swamps. The Sundarbans are home to approximately 160 Bengal tigers known for their superb swimming skills and outstanding adaptation to the tidal mangrove environment. The tigers move with confidence through saline water and thick cover, personifying the adaptability and tenacity of the species in one of the Earth’s toughest environments.

Based on the 2022 National Tiger Census, India is home to an estimated 3,682 tigers — higher than the 2018 count of 2,967 — a major conservation achievement. Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Uttarakhand, and Maharashtra top the list in terms of numbers, although population densities are different according to habitat quality and prey base.

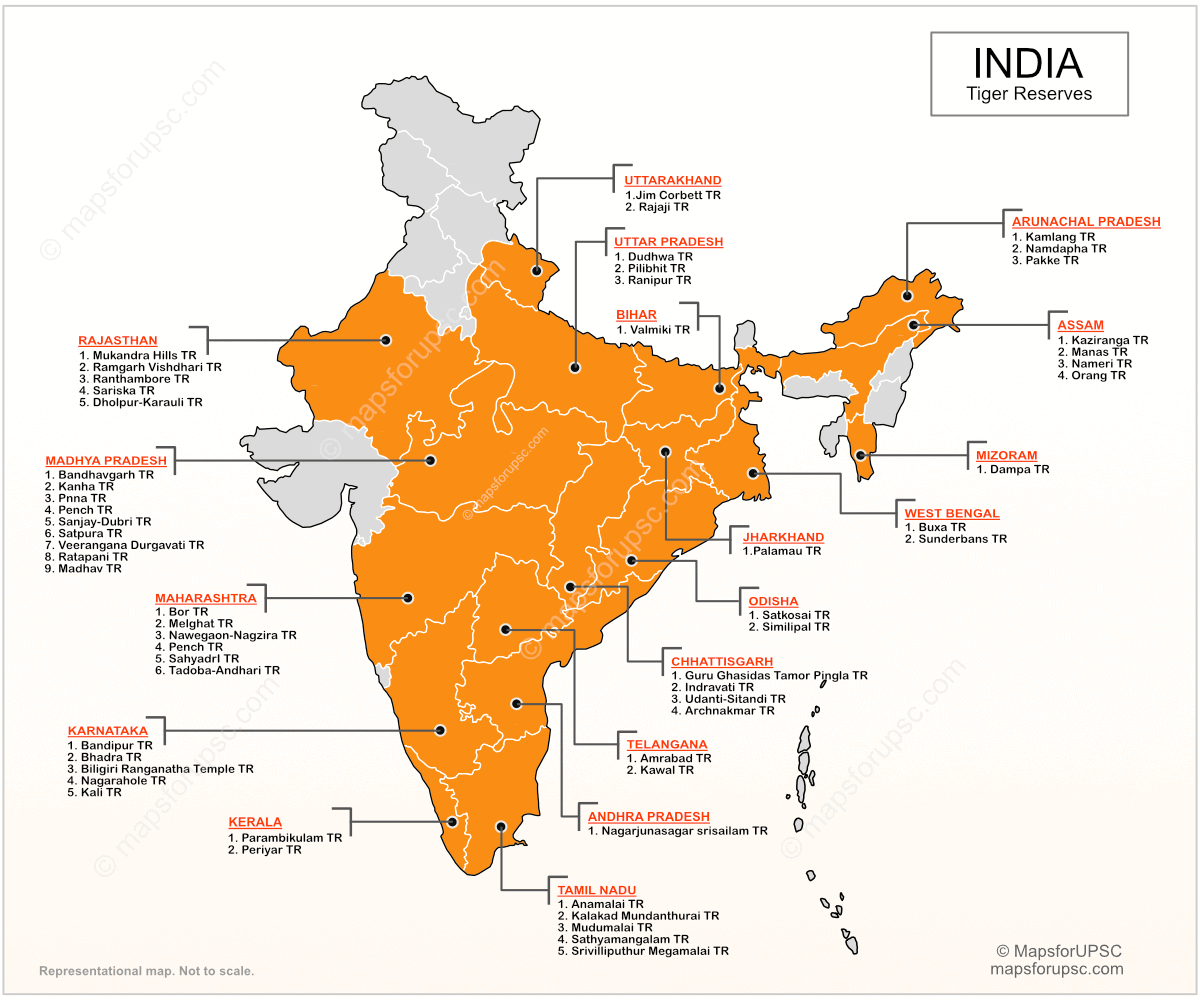

At the time of 2025, the nation will have 58 tiger reserves recognized under the Project Tiger / NTCA scheme spread across over 75,000 square kilometers of protected landscape — a reflection of India’s continuing dedication to tiger revival.

Tiger reserves, protected areas, and the Project Tiger network

Project Tiger was the origin of tiger reserves that incorporated core and buffer zones and aimed to provide targeted management and anti-poaching resources. From the project’s initiation in 1973 with an initial nine reserves, the network has expanded considerably.

Number of tiger reserves: The officially recognized Project Tiger / NTCA network of tiger reserves has developed over time, with official synopsis and compilation lists suggesting that approximately 58 reserves were recognized in recent years (2024-2025) with the addition of new reserves and re-classifications. What is common to all reserves is that they comprise a complex matrix of protected “core,” “buffer” and landscape features in order to maintain viable populations of tigers and ecological connectivity to one another.

Area and distribution: Project Tiger area now spans many thousands of square kilometres (core + buffer) and accounts for approximately 2-2.5% of India’s land area in formally designated “reserves”; however, additional conservation practice outside the designated reserves exists with protected forests, community lands, and privately managed area conservation.

Ecological Role

As apex predators, Bengal tigers are an important part of maintaining healthy forest ecosystems. By predating on large herbivores including chital, sambar, nilgai, gaur, and water buffalo, tigers help regulate herbivore population sizes and behaviors, diminish overgrazing, and promote natural forest regeneration. With this ecological balance, tigers affect vegetation structure, seedling recruitment, and even hydrology and soil stability, arguably making the Bengal tiger the consummate keystone species.

Tigers are regarded as key ecological indicators—their survival reflects India’s forest health in general. Tigers’ preservation also protects the millions of other species that coexist with them, such as deer, wild boar, barasingha, elephants, and varied vegetation. In addition to this, the preservation of large, intact tiger landscapes through protected areas helps maintain essential ecosystem services, including water provisioning, carbon sequestration, and culturally valued biodiversity that is vital for both ecological and human well-being. To this effect, the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) has sought to place more importance on valuing these ecosystem services towards ensuring policy and planning for long-term protection of the habitats.

Threats — what continues to endanger tigers

Despite conservation gains, Bengal tigers face persistent, often interacting threats:

- Poaching and illegal trade: Tigers and their parts continue to be targeted for illegal markets. Organized trafficking networks, cross-border demand, and the high value of bones, skins, and derivatives place constant pressure on populations. Law enforcement, international cooperation, forensic, and sustained anti-poaching patrols are necessary to counter these networks.

- Habitat loss and fragmentation: Agricultural expansion, mining, infrastructure (roads, railways, linear developments), and urbanisation fragment tiger habitats, undermine connectivity, and increase edge effects. Fragmentation reduces dispersal opportunities, heightens human–tiger encounters, and raises genetic risks for isolated populations.

- Human–wildlife conflict: Tigers that enter human-dominated landscapes for prey or movement can kill livestock and, rarely, people; such incidents can trigger retaliatory killings and erode local support for conservation. Mitigation requires compensation schemes, improved husbandry, early warning systems, and community incentives for coexistence.

- Climate change, with acute threats in low-lying areas: The Sundarbans — the world’s largest mangrove belt shared between India and Bangladesh and a unique tiger stronghold — is highly vulnerable to sea-level rise, salinity intrusion, and increased cyclone intensity. Modelling shows that even modest sea-level rise scenarios could dramatically erode suitable tiger habitat in the Sundarbans, with large implications for local tiger numbers and associated human communities. Adaptation planning is now an urgent conservation priority for such coastal landscapes.

- Governance and capacity gaps: Effective protection requires trained personnel, sustained funding, clear inter-agency coordination (across forestry, wildlife, police, customs, and local administration), and corruption-resistant systems — all of which can be uneven at the local and state levels. High-profile local failures (for example, earlier poaching-driven local extinctions) underscore the need for vigilance.

Conservation Efforts

India’s conservation response is notable for integrating legal protection, landscape planning, modern science, and community engagement. Key elements include:

- Legislation and institutions: The Wildlife (Protection) Act (1972) provides the legal framework; the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) oversees Project Tiger, issues guidelines, and coordinates national monitoring and policy.

- Protected area management and anti-poaching: Dedicated tiger reserves use a core–buffer management model, staffing for anti-poaching units, and targeted intelligence operations to disrupt illegal hunting and trafficking. Forensics (DNA analysis), criminal prosecution, and cross-border cooperation are increasingly central.

- Systematic monitoring and rigorous science: Large-scale camera-trap programmes and photographic capture–recapture methods underpin national estimates; GIS and remote sensing map habitat change and connectivity; genetic tools enable population assignment and forensic evidence in crime cases. The 2022 national assessment used these methods to produce robust, repeatable estimates.

- Landscape-level conservation & corridors: Maintaining connectivity between reserves through habitat corridors and reducing fragmentation is essential for gene flow and dispersal of young tigers. NTCA and other partners have prioritized corridor mapping and restoration in many key landscapes.

- Community engagement & livelihoods: Long-term success depends on local communities seeing tangible benefits from conservation. Programs that compensate livestock losses, create employment through regulated ecotourism, and involve communities in monitoring strengthen co-management and reduce incentives for illegal activities.

Success stories, setbacks, and lessons

Successes

- A national trend toward recovery over many landscapes has existed since the early 2000s – a result of ongoing funding, reserve management, monitoring, and enforcement. The 2022 national estimate (3,682) is evidence of this positive trajectory at a national level. Regions, for example, parts of Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and some southern states have reported strong or improving tiger populations, and where landscapes and enforcement are high.

Setbacks and cautionary examples

- The local extinction of the Sariska Tiger Reserve (Rajasthan) in 2004–2006 due to coordinated poaching serves as a very strong illustration of how quickly populations can be lost in the face of governance collapse. There has been some return to the Sariska population due to translocations and management action – it is an important story that not only demonstrates risks but also shows the potential for recovery with appropriate action; a recent report (2025) shows a significant population increase in Sariska, a measure of rehabilitation success.

Lessons

- Progress at the national level can potentially hide fragility at the local level. Thus, conservation needs to take place simultaneously at multiple scales: local enforcement and community support, connectivity across sub-state and national landscapes, and climate adaptation planning to vulnerable habitats. Political will and funding over the long term are essential and non-negotiable.

Special focus: the Sundarbans and climate vulnerability

The Sundarbans—the largest juxtaposed mangrove forest and unique habitat for tigers as they swim and hunt across tidal channels—is a high priority for conservation as a hotspot for risk due to climate change. Modeling has indicated that both rising sea levels and storms will significantly threaten suitable tiger habitat in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh and India—potentially compromising breeding populations and increasing human-tiger conflict, as wildlife and humans are displaced. These responses must be coordinated to address, e.g., integrated coastal management, habitat restoration, human-relocation strategies where appropriate, and cross-border research and planning.

Cultural importance and national identity

The tiger, apart from its ecological role, has a cultural significance in South Asia: from motifs seen across archaeological sites, in classical and folk art, as the vahana of the Goddess Durga, to being a symbol in royal heraldry, stamps, and currency. This cultural significance has been utilized as a powerful leverage for public and political support for conservation. The symbolism of the tiger — strength, protection, dignity — still finds its way into conservation narratives and public education concerning the conservation of biodiversity.

Safeguarding the Future

The Royal Bengal Tiger represents India’s natural heritage and is an indicator of the health of its biggest wild areas. India’s conservation history shows that populations can recover through disciplined management, science, enforcement of laws, and local community involvement. While progress is possible, there are also emerging threats – climate change, more sophisticated trafficking networks, and ongoing habitat fragmentation. The future of the tiger depends on sustained political will, landscape-scale planning, cross-sectoral partnerships, and inclusive approaches that balance human needs and wildlife conservation outcomes. Protecting the tiger is not just about preserving the icon: it is about protecting ecological and social systems upon which both biodiversity and people depend.

Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@BhartiSanskriti-BS